This is a blog about the Bronte Sisters, Charlotte, Emily and Anne. And their father Patrick, their mother Maria and their brother Branwell. About their pets, their friends, the parsonage (their house), Haworth the town in which they lived, the moors they loved so much, the Victorian era in which they lived.

I've dreamt in my life dreams that have stayed with me ever after, and changed my ideas: they've gone through and through me, like wine through water, and altered the color of my mind.

Emily BronteWuthering Heights

vrijdag 27 september 2013

woensdag 25 september 2013

Dr Robert Barnard, a former chairman of the Bronte Society, author and compiler of the Bronte Encyclopaedia, has died.

The Telegraph and Argus has published an obituary of Robert Barnard:

A former chairman of the Bronte Society, author and compiler of the Bronte Encyclopaedia, has died.

Dr Robert Barnard was also a prolific crime writer as well as being a “mine of information” on Haworth’s most famous residents.

He died on Friday at Grove Court Nursing Home in Leeds, at 76.

Along with his wife Louise, he compiled The Bronte Encyclopaedia in 2007, referred to by the society as “a cornerstone for modern Bronte scholarship.”

He was chair of the society twice and also wrote a book on Emily Bronte’s life.

Essex born and Leeds based, Mr Barnard spent lots of time at the Bronte Parsonage and around Haworth.

He started writing crime novels in the 1970s, writing over 40 books and short stories and receiving the Cartier Diamond Dagger award in 2003 for services to crime fiction.

Marcel Berlins, critic at The Times, called Mr Barnard: “One of our most original and versatile bloodspillers.”

The Bronte Society’s Richard Wilcocks said: “Well known in the Bronte Society, he was a professor, a scholar and an award-winning crime writer.” bronteblog

From the Treasure Trove: warming pan.

From the Treasure Trove: warming pan.

We recently received this warming pan on a loan.

On cold nights, the Brontes would have filled it with coal to keep their beds warm.

Bronte Society e-newslett

Another item on loan to us is the Brontës’ brass warming pan, which was sold at the 1861 sale of the Brontës' posessions after Patrick Brontë's death. The Brontës would have used it to warm their sheets before getting into bed and we're delighted to have an object that would have brought the Brontës so much comfort in cold times! It is in need of conservation work so won't be going on display right away. We will keep you updated on its progress.

Another item on loan to us is the Brontës’ brass warming pan, which was sold at the 1861 sale of the Brontës' posessions after Patrick Brontë's death. The Brontës would have used it to warm their sheets before getting into bed and we're delighted to have an object that would have brought the Brontës so much comfort in cold times! It is in need of conservation work so won't be going on display right away. We will keep you updated on its progress.

dinsdag 24 september 2013

"After a struggle of twenty minutes... Branwell started convulsively, almost to his feet, and fell back dead into his father's arms..."

From the Treasure Trove: Branwell's funeral card.

"After a struggle of twenty minutes... Branwell started convulsively, almost to his feet, and fell back dead into his father's arms..."

(p.670, The Brontes, Juliet Barker) facebook/Bronte-Parsonage-Museum

---------------------------

The cause of Branwell's death was stated in his death certificate as chronic bronchitis and marasmus (wasting of the body). Charlotte said of her brother "I seemed to receive an oppressive revelation of the feebleness of humanity; of the inadequacy of even genius to lead to true greatness if unaided by religion and principle. When the struggle was over.....all his errors, all his vices, seemed nothing to me in that moment....he is at rest, and that comforts us all. Long before he quitted this world, life had no happiness for him." bronte

maandag 23 september 2013

Emily’s paint box, Patrick’s glasses, the Exhibition Room In the 1970s

From the Treasure Trove: Emily’s paint box

From the Treasure Trove: Patrick’s glasses.

In her book about The Brontes, Juliet Barker writes:

“Charlotte was shocked on her return to Haworth at the beginning of 1844 to discover that, despite his activity, her father’s health had deteriorated rapidly in her absence. He was now sixty-six years of age: his eyesight was failing rapidly and he had to face the prospect that he might soon go blind”.

In the 1970s the Exhibition Room looked like THIS:

zondag 22 september 2013

But I am very very sorry that my inadvertent blunder should have made his name and affairs a subject for common gossip......

The dedication here referred to is that to Thackeray. People had been already suggesting that Jane Eyre might have been written by Thackeray under a pseudonym; others had implied, knowing that there was ‘something about a woman’ in Thackeray’s life, that it was written by a mistress of the great novelist. Indeed, the Quarterly had half hinted as much. Currer Bell, knowing nothing of the gossip of London, had dedicated her book in single-minded enthusiasm. Her distress was keen when it was revealed to her that the wife of Mr. Thackeray, like the wife of Rochester in Jane Eyre, was of unsound mind. However, a correspondence with him would seem to have ended amicably enough. [408]

‘Dear Sir,—I need not tell you that when I saw Mr. Thackeray’s letter inclosed under your cover, the sight made me very happy. It was some time before I dared open it, lest my pleasure in receiving it should be mixed with pain on learning its contents—lest, in short, the dedication should have been, in some way, unacceptable to him.

‘Dear Sir,—I need not tell you that when I saw Mr. Thackeray’s letter inclosed under your cover, the sight made me very happy. It was some time before I dared open it, lest my pleasure in receiving it should be mixed with pain on learning its contents—lest, in short, the dedication should have been, in some way, unacceptable to him.

TO W. S. WILLIAMS

‘Haworth, January 28th, 1848.

‘Dear Sir,—I need not tell you that when I saw Mr. Thackeray’s letter inclosed under your cover, the sight made me very happy. It was some time before I dared open it, lest my pleasure in receiving it should be mixed with pain on learning its contents—lest, in short, the dedication should have been, in some way, unacceptable to him.

‘Dear Sir,—I need not tell you that when I saw Mr. Thackeray’s letter inclosed under your cover, the sight made me very happy. It was some time before I dared open it, lest my pleasure in receiving it should be mixed with pain on learning its contents—lest, in short, the dedication should have been, in some way, unacceptable to him.

‘And, to tell you the truth, I fear this must have been the case; he does not say so, his letter is most friendly in its noble simplicity, but he apprises me, at the commencement, of a circumstance which both surprised and dismayed me.

‘I suppose it is no indiscretion to tell you this circumstance, p. 409for you doubtless know it already. It appears that his private position is in some points similar to that I have ascribed to Mr. Rochester; that thence arose a report that Jane Eyre had been written by a governess in his family, and that the dedication coming now has confirmed everybody in the surmise.

‘Well may it be said that fact is often stranger than fiction! The coincidence struck me as equally unfortunate and extraordinary. Of course I knew nothing whatever of Mr. Thackeray’s domestic concerns, he existed for me only as an author. Of all regarding his personality, station, connections, private history, I was, and am still in a great measure, totally in the dark; but I am very very sorry that my inadvertent blunder should have made his name and affairs a subject for common gossip.

‘The very fact of his not complaining at all and addressing me with such kindness, notwithstanding the pain and annoyance I must have caused him, increases my chagrin. I could not half express my regret to him in my answer, for I was restrained by the consciousness that that regret was just worth nothing at all—quite valueless for healing the mischief I had done.

‘Can you tell me anything more on this subject? or can you guess in what degree the unlucky coincidence would affect him—whether it would pain him much and deeply; for he says so little himself on the topic, I am at a loss to divine the exact truth—but I fear.

‘Do not think, my dear sir, from my silence respecting the advice you have, at different times, given me for my future literary guidance, that I am heedless of, or indifferent to, your kindness. I keep your letters and not unfrequently refer to them. Circumstances may render it impracticable for me to act up to the letter of what you counsel, but I think I comprehend the spirit of your precepts, and trust I shall be able to profit thereby. Details, situations which I do not understand and cannot personally inspect, I would not for the world meddle with, lest I should make even a more ridiculous mess of the matter than Mrs. Trollope did in her Factory Boy. Besides, not one feeling on any subject, public or private, will I ever p. 410affect that I do not really experience. Yet though I must limit my sympathies; though my observation cannot penetrate where the very deepest political and social truths are to be learnt; though many doors of knowledge which are open for you are for ever shut for me; though I must guess and calculate and grope my way in the dark, and come to uncertain conclusions unaided and alone where such writers as Dickens and Thackeray, having access to the shrine and image of Truth, have only to go into the temple, lift the veil a moment, and come out and say what they have seen—yet with every disadvantage, I mean still, in my own contracted way, to do my best. Imperfect my best will be, and poor, and compared with the works of the true masters—of that greatest modern master Thackeray in especial (for it is him I at heart reverence with all my strength)—it will be trifling, but I trust not affected or counterfeit.—Believe me, my dear sir, yours with regard and respect,

Currer Bell.’

Abonneren op:

Posts (Atom)

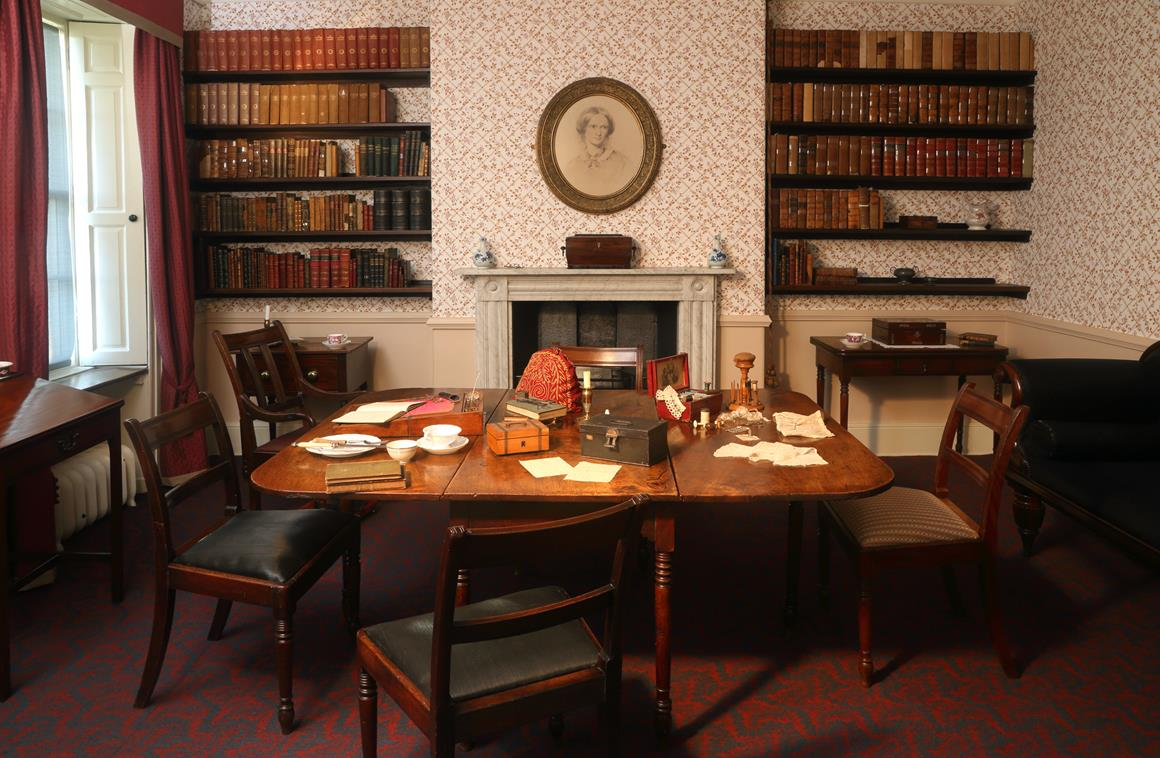

The Parlour

Parsonage

Charlotte Bronte

Presently the door opened, and in came a superannuated mastiff, followed by an old gentleman very like Miss Bronte, who shook hands with us, and then went to call his daughter. A long interval, during which we coaxed the old dog, and looked at a picture of Miss Bronte, by Richmond, the solitary ornament of the room, looking strangely out of place on the bare walls, and at the books on the little shelves, most of them evidently the gift of the authors since Miss Bronte's celebrity. Presently she came in, and welcomed us very kindly, and took me upstairs to take off my bonnet, and herself brought me water and towels. The uncarpeted stone stairs and floors, the old drawers propped on wood, were all scrupulously clean and neat. When we went into the parlour again, we began talking very comfortably, when the door opened and Mr. Bronte looked in; seeing his daughter there, I suppose he thought it was all right, and he retreated to his study on the opposite side of the passage; presently emerging again to bring W---- a country newspaper. This was his last appearance till we went. Miss Bronte spoke with the greatest warmth of Miss Martineau, and of the good she had gained from her. Well! we talked about various things; the character of the people, - about her solitude, etc., till she left the room to help about dinner, I suppose, for she did not return for an age. The old dog had vanished; a fat curly-haired dog honoured us with his company for some time, but finally manifested a wish to get out, so we were left alone. At last she returned, followed by the maid and dinner, which made us all more comfortable; and we had some very pleasant conversation, in the midst of which time passed quicker than we supposed, for at last W---- found that it was half-past three, and we had fourteen or fifteen miles before us. So we hurried off, having obtained from her a promise to pay us a visit in the spring... ------------------- "She cannot see well, and does little beside knitting. The way she weakened her eyesight was this: When she was sixteen or seventeen, she wanted much to draw; and she copied nimini-pimini copper-plate engravings out of annuals, ('stippling,' don't the artists call it?) every little point put in, till at the end of six months she had produced an exquisitely faithful copy of the engraving. She wanted to learn to express her ideas by drawing. After she had tried to draw stories, and not succeeded, she took the better mode of writing; but in so small a hand, that it is almost impossible to decipher what she wrote at this time.

I asked her whether she had ever taken opium, as the description given of its effects in Villette was so exactly like what I had experienced, - vivid and exaggerated presence of objects, of which the outlines were indistinct, or lost in golden mist, etc. She replied, that she had never, to her knowledge, taken a grain of it in any shape, but that she had followed the process she always adopted when she had to describe anything which had not fallen within her own experience; she had thought intently on it for many and many a night before falling to sleep, - wondering what it was like, or how it would be, - till at length, sometimes after the progress of her story had been arrested at this one point for weeks, she wakened up in the morning with all clear before her, as if she had in reality gone through the experience, and then could describe it, word for word, as it had happened. I cannot account for this psychologically; I only am sure that it was so, because she said it. ----------------------She thought much of her duty, and had loftier and clearer notions of it than most people, and held fast to them with more success. It was done, it seems to me, with much more difficulty than people have of stronger nerves, and better fortunes. All her life was but labour and pain; and she never threw down the burden for the sake of present pleasure. I don't know what use you can make of all I have said. I have written it with the strong desire to obtain appreciation for her. Yet, what does it matter? She herself appealed to the world's judgement for her use of some of the faculties she had, - not the best, - but still the only ones she could turn to strangers' benefit. They heartily, greedily enjoyed the fruits of her labours, and then found out she was much to be blamed for possessing such faculties. Why ask for a judgement on her from such a world?" elizabeth gaskell/charlotte bronte

I asked her whether she had ever taken opium, as the description given of its effects in Villette was so exactly like what I had experienced, - vivid and exaggerated presence of objects, of which the outlines were indistinct, or lost in golden mist, etc. She replied, that she had never, to her knowledge, taken a grain of it in any shape, but that she had followed the process she always adopted when she had to describe anything which had not fallen within her own experience; she had thought intently on it for many and many a night before falling to sleep, - wondering what it was like, or how it would be, - till at length, sometimes after the progress of her story had been arrested at this one point for weeks, she wakened up in the morning with all clear before her, as if she had in reality gone through the experience, and then could describe it, word for word, as it had happened. I cannot account for this psychologically; I only am sure that it was so, because she said it. ----------------------She thought much of her duty, and had loftier and clearer notions of it than most people, and held fast to them with more success. It was done, it seems to me, with much more difficulty than people have of stronger nerves, and better fortunes. All her life was but labour and pain; and she never threw down the burden for the sake of present pleasure. I don't know what use you can make of all I have said. I have written it with the strong desire to obtain appreciation for her. Yet, what does it matter? She herself appealed to the world's judgement for her use of some of the faculties she had, - not the best, - but still the only ones she could turn to strangers' benefit. They heartily, greedily enjoyed the fruits of her labours, and then found out she was much to be blamed for possessing such faculties. Why ask for a judgement on her from such a world?" elizabeth gaskell/charlotte bronte

Poem: No coward soul is mine

No coward soul is mine,

No trembler in the worlds storm-troubled sphere:

I see Heavens glories shine,

And faith shines equal, arming me from fear.

O God within my breast.

Almighty, ever-present Deity!

Life -- that in me has rest,

As I -- Undying Life -- have power in Thee!

Vain are the thousand creeds

That move mens hearts: unutterably vain;

Worthless as withered weeds,

Or idlest froth amid the boundless main,

To waken doubt in one

Holding so fast by Thine infinity;

So surely anchored on

The steadfast Rock of immortality.

With wide-embracing love

Thy Spirit animates eternal years,

Pervades and broods above,

Changes, sustains, dissolves, creates, and rears.

Though earth and man were gone,

And suns and universes ceased to be,

And Thou wert left alone,

Every existence would exist in Thee.

There is not room for Death,

Nor atom that his might could render void:

Thou -- Thou art Being and Breath,

And what Thou art may never be destroyed.

-- Emily Bronte

No trembler in the worlds storm-troubled sphere:

I see Heavens glories shine,

And faith shines equal, arming me from fear.

O God within my breast.

Almighty, ever-present Deity!

Life -- that in me has rest,

As I -- Undying Life -- have power in Thee!

Vain are the thousand creeds

That move mens hearts: unutterably vain;

Worthless as withered weeds,

Or idlest froth amid the boundless main,

To waken doubt in one

Holding so fast by Thine infinity;

So surely anchored on

The steadfast Rock of immortality.

With wide-embracing love

Thy Spirit animates eternal years,

Pervades and broods above,

Changes, sustains, dissolves, creates, and rears.

Though earth and man were gone,

And suns and universes ceased to be,

And Thou wert left alone,

Every existence would exist in Thee.

There is not room for Death,

Nor atom that his might could render void:

Thou -- Thou art Being and Breath,

And what Thou art may never be destroyed.

-- Emily Bronte

Family tree

The Bronte Family

Grandparents - paternal

Hugh Brunty was born 1755 and died circa 1808. He married Eleanor McClory, known as Alice in 1776.

Grandparents - maternal

Thomas Branwell (born 1746 died 5th April 1808) was married in 1768 to Anne Carne (baptised 27th April 1744 and died 19th December 1809).

Parents

Father was Patrick Bronte, the eldest of 10 children born to Hugh Brunty and Eleanor (Alice) McClory. He was born 17th March 1777 and died on 7th June 1861. Mother was Maria Branwell, who was born on 15th April 1783 and died on 15th September 1821.

Maria had a sister, Elizabeth who was known as Aunt Branwell. She was born in 1776 and died on 29th October 1842.

Patrick Bronte married Maria Branwell on 29th December 1812.

The Bronte Children

Patrick and Maria Bronte had six children.

The first child was Maria, who was born in 1814 and died on 6th June 1825.

The second daughter, Elizabeth was born on 8th February 1815 and died shortly after Maria on 15th June 1825. Charlotte was the third daughter, born on 21st April 1816.

Charlotte married Arthur Bell Nicholls (born 1818) on 29th June 1854. Charlotte died on 31st March 1855. Arthur lived until 2nd December 1906.

The first and only son born to Patrick and Maria was Patrick Branwell, who was born on 26th June 1817 and died on 24th September 1848.

Emily Jane, the fourth daughter was born on 30th July 1818 and died on 19th December 1848.

The sixth and last child was Anne, born on 17th January 1820 who died on 28th May 1849.

Grandparents - paternal

Hugh Brunty was born 1755 and died circa 1808. He married Eleanor McClory, known as Alice in 1776.

Grandparents - maternal

Thomas Branwell (born 1746 died 5th April 1808) was married in 1768 to Anne Carne (baptised 27th April 1744 and died 19th December 1809).

Parents

Father was Patrick Bronte, the eldest of 10 children born to Hugh Brunty and Eleanor (Alice) McClory. He was born 17th March 1777 and died on 7th June 1861. Mother was Maria Branwell, who was born on 15th April 1783 and died on 15th September 1821.

Maria had a sister, Elizabeth who was known as Aunt Branwell. She was born in 1776 and died on 29th October 1842.

Patrick Bronte married Maria Branwell on 29th December 1812.

The Bronte Children

Patrick and Maria Bronte had six children.

The first child was Maria, who was born in 1814 and died on 6th June 1825.

The second daughter, Elizabeth was born on 8th February 1815 and died shortly after Maria on 15th June 1825. Charlotte was the third daughter, born on 21st April 1816.

Charlotte married Arthur Bell Nicholls (born 1818) on 29th June 1854. Charlotte died on 31st March 1855. Arthur lived until 2nd December 1906.

The first and only son born to Patrick and Maria was Patrick Branwell, who was born on 26th June 1817 and died on 24th September 1848.

Emily Jane, the fourth daughter was born on 30th July 1818 and died on 19th December 1848.

The sixth and last child was Anne, born on 17th January 1820 who died on 28th May 1849.

Top Withens in the snow.

Blogarchief

-

►

2024

(10)

- ► 03/17 - 03/24 (1)

- ► 02/18 - 02/25 (1)

- ► 01/21 - 01/28 (5)

- ► 01/14 - 01/21 (1)

- ► 01/07 - 01/14 (2)

-

►

2023

(9)

- ► 11/26 - 12/03 (1)

- ► 11/19 - 11/26 (1)

- ► 07/23 - 07/30 (1)

- ► 05/28 - 06/04 (1)

- ► 05/14 - 05/21 (1)

- ► 05/07 - 05/14 (1)

- ► 04/02 - 04/09 (1)

- ► 03/05 - 03/12 (1)

- ► 02/05 - 02/12 (1)

-

►

2022

(27)

- ► 12/25 - 01/01 (1)

- ► 12/04 - 12/11 (1)

- ► 11/20 - 11/27 (1)

- ► 11/13 - 11/20 (2)

- ► 10/30 - 11/06 (2)

- ► 10/23 - 10/30 (2)

- ► 10/09 - 10/16 (2)

- ► 07/17 - 07/24 (1)

- ► 06/12 - 06/19 (1)

- ► 06/05 - 06/12 (1)

- ► 05/22 - 05/29 (2)

- ► 02/27 - 03/06 (1)

- ► 02/20 - 02/27 (1)

- ► 02/13 - 02/20 (7)

- ► 01/16 - 01/23 (2)

-

►

2021

(47)

- ► 12/19 - 12/26 (1)

- ► 12/12 - 12/19 (1)

- ► 11/28 - 12/05 (1)

- ► 11/21 - 11/28 (2)

- ► 11/14 - 11/21 (1)

- ► 10/31 - 11/07 (2)

- ► 08/15 - 08/22 (1)

- ► 08/08 - 08/15 (1)

- ► 08/01 - 08/08 (1)

- ► 07/25 - 08/01 (1)

- ► 07/18 - 07/25 (1)

- ► 07/11 - 07/18 (1)

- ► 06/20 - 06/27 (3)

- ► 06/13 - 06/20 (2)

- ► 06/06 - 06/13 (3)

- ► 05/30 - 06/06 (7)

- ► 05/23 - 05/30 (8)

- ► 05/02 - 05/09 (2)

- ► 04/18 - 04/25 (4)

- ► 04/11 - 04/18 (1)

- ► 03/28 - 04/04 (2)

- ► 01/03 - 01/10 (1)

-

►

2020

(34)

- ► 12/20 - 12/27 (1)

- ► 12/06 - 12/13 (5)

- ► 11/08 - 11/15 (2)

- ► 11/01 - 11/08 (1)

- ► 10/11 - 10/18 (1)

- ► 10/04 - 10/11 (1)

- ► 09/06 - 09/13 (4)

- ► 08/16 - 08/23 (3)

- ► 08/02 - 08/09 (2)

- ► 07/12 - 07/19 (1)

- ► 07/05 - 07/12 (1)

- ► 06/28 - 07/05 (1)

- ► 04/19 - 04/26 (1)

- ► 03/22 - 03/29 (1)

- ► 02/09 - 02/16 (2)

- ► 01/26 - 02/02 (2)

- ► 01/12 - 01/19 (3)

- ► 01/05 - 01/12 (2)

-

►

2019

(34)

- ► 12/29 - 01/05 (2)

- ► 12/15 - 12/22 (1)

- ► 12/08 - 12/15 (1)

- ► 12/01 - 12/08 (3)

- ► 11/17 - 11/24 (2)

- ► 11/10 - 11/17 (2)

- ► 11/03 - 11/10 (1)

- ► 10/13 - 10/20 (2)

- ► 10/06 - 10/13 (1)

- ► 09/22 - 09/29 (1)

- ► 09/08 - 09/15 (1)

- ► 09/01 - 09/08 (3)

- ► 08/25 - 09/01 (2)

- ► 07/21 - 07/28 (1)

- ► 06/30 - 07/07 (2)

- ► 06/09 - 06/16 (1)

- ► 05/26 - 06/02 (1)

- ► 04/14 - 04/21 (1)

- ► 04/07 - 04/14 (1)

- ► 03/03 - 03/10 (1)

- ► 02/17 - 02/24 (2)

- ► 02/10 - 02/17 (1)

- ► 02/03 - 02/10 (1)

-

►

2018

(82)

- ► 12/30 - 01/06 (2)

- ► 12/23 - 12/30 (4)

- ► 12/16 - 12/23 (2)

- ► 11/25 - 12/02 (1)

- ► 11/18 - 11/25 (2)

- ► 11/11 - 11/18 (3)

- ► 11/04 - 11/11 (1)

- ► 10/28 - 11/04 (3)

- ► 10/21 - 10/28 (3)

- ► 10/07 - 10/14 (4)

- ► 09/23 - 09/30 (1)

- ► 08/26 - 09/02 (1)

- ► 08/19 - 08/26 (1)

- ► 08/05 - 08/12 (1)

- ► 07/29 - 08/05 (8)

- ► 07/22 - 07/29 (6)

- ► 06/24 - 07/01 (2)

- ► 06/17 - 06/24 (2)

- ► 06/10 - 06/17 (4)

- ► 06/03 - 06/10 (5)

- ► 05/27 - 06/03 (3)

- ► 05/20 - 05/27 (1)

- ► 05/13 - 05/20 (1)

- ► 05/06 - 05/13 (1)

- ► 04/29 - 05/06 (1)

- ► 04/22 - 04/29 (1)

- ► 04/15 - 04/22 (1)

- ► 04/08 - 04/15 (2)

- ► 04/01 - 04/08 (1)

- ► 03/25 - 04/01 (1)

- ► 03/18 - 03/25 (3)

- ► 03/11 - 03/18 (2)

- ► 03/04 - 03/11 (2)

- ► 02/11 - 02/18 (2)

- ► 01/14 - 01/21 (4)

-

►

2017

(69)

- ► 12/31 - 01/07 (2)

- ► 12/24 - 12/31 (1)

- ► 12/17 - 12/24 (1)

- ► 12/10 - 12/17 (2)

- ► 12/03 - 12/10 (4)

- ► 11/26 - 12/03 (1)

- ► 11/19 - 11/26 (5)

- ► 11/12 - 11/19 (2)

- ► 10/08 - 10/15 (2)

- ► 10/01 - 10/08 (2)

- ► 09/10 - 09/17 (2)

- ► 08/27 - 09/03 (2)

- ► 07/30 - 08/06 (1)

- ► 07/23 - 07/30 (1)

- ► 07/16 - 07/23 (3)

- ► 07/09 - 07/16 (1)

- ► 06/25 - 07/02 (3)

- ► 06/04 - 06/11 (1)

- ► 05/28 - 06/04 (1)

- ► 05/07 - 05/14 (2)

- ► 04/30 - 05/07 (2)

- ► 04/23 - 04/30 (1)

- ► 04/16 - 04/23 (2)

- ► 04/09 - 04/16 (2)

- ► 04/02 - 04/09 (3)

- ► 03/26 - 04/02 (1)

- ► 03/19 - 03/26 (1)

- ► 03/05 - 03/12 (4)

- ► 02/12 - 02/19 (1)

- ► 02/05 - 02/12 (4)

- ► 01/29 - 02/05 (1)

- ► 01/22 - 01/29 (2)

- ► 01/15 - 01/22 (2)

- ► 01/08 - 01/15 (2)

- ► 01/01 - 01/08 (2)

-

►

2016

(126)

- ► 12/25 - 01/01 (3)

- ► 12/18 - 12/25 (4)

- ► 12/04 - 12/11 (1)

- ► 11/27 - 12/04 (4)

- ► 11/20 - 11/27 (1)

- ► 11/13 - 11/20 (3)

- ► 11/06 - 11/13 (8)

- ► 10/30 - 11/06 (1)

- ► 10/23 - 10/30 (1)

- ► 10/16 - 10/23 (3)

- ► 10/09 - 10/16 (2)

- ► 10/02 - 10/09 (3)

- ► 09/11 - 09/18 (1)

- ► 08/28 - 09/04 (2)

- ► 08/21 - 08/28 (3)

- ► 08/07 - 08/14 (1)

- ► 07/31 - 08/07 (1)

- ► 07/24 - 07/31 (4)

- ► 07/17 - 07/24 (3)

- ► 07/03 - 07/10 (1)

- ► 06/26 - 07/03 (4)

- ► 06/19 - 06/26 (3)

- ► 06/12 - 06/19 (2)

- ► 06/05 - 06/12 (8)

- ► 05/29 - 06/05 (3)

- ► 05/22 - 05/29 (3)

- ► 05/08 - 05/15 (3)

- ► 05/01 - 05/08 (2)

- ► 04/24 - 05/01 (1)

- ► 04/17 - 04/24 (6)

- ► 04/10 - 04/17 (2)

- ► 04/03 - 04/10 (1)

- ► 03/27 - 04/03 (6)

- ► 03/20 - 03/27 (4)

- ► 03/13 - 03/20 (7)

- ► 03/06 - 03/13 (6)

- ► 02/28 - 03/06 (3)

- ► 02/21 - 02/28 (1)

- ► 02/14 - 02/21 (2)

- ► 02/07 - 02/14 (2)

- ► 01/31 - 02/07 (2)

- ► 01/17 - 01/24 (2)

- ► 01/10 - 01/17 (1)

- ► 01/03 - 01/10 (2)

-

►

2015

(192)

- ► 12/27 - 01/03 (4)

- ► 12/20 - 12/27 (4)

- ► 12/13 - 12/20 (6)

- ► 12/06 - 12/13 (3)

- ► 11/29 - 12/06 (1)

- ► 11/22 - 11/29 (4)

- ► 11/15 - 11/22 (4)

- ► 11/08 - 11/15 (8)

- ► 11/01 - 11/08 (2)

- ► 10/25 - 11/01 (4)

- ► 10/18 - 10/25 (2)

- ► 10/11 - 10/18 (2)

- ► 10/04 - 10/11 (2)

- ► 09/27 - 10/04 (4)

- ► 09/20 - 09/27 (3)

- ► 09/13 - 09/20 (2)

- ► 09/06 - 09/13 (2)

- ► 08/30 - 09/06 (3)

- ► 08/23 - 08/30 (1)

- ► 08/16 - 08/23 (4)

- ► 08/09 - 08/16 (2)

- ► 08/02 - 08/09 (4)

- ► 07/26 - 08/02 (5)

- ► 07/19 - 07/26 (2)

- ► 07/12 - 07/19 (3)

- ► 07/05 - 07/12 (1)

- ► 06/21 - 06/28 (1)

- ► 06/14 - 06/21 (10)

- ► 06/07 - 06/14 (2)

- ► 05/31 - 06/07 (6)

- ► 05/24 - 05/31 (4)

- ► 05/17 - 05/24 (2)

- ► 05/10 - 05/17 (2)

- ► 05/03 - 05/10 (4)

- ► 04/26 - 05/03 (5)

- ► 04/19 - 04/26 (7)

- ► 04/12 - 04/19 (3)

- ► 04/05 - 04/12 (3)

- ► 03/29 - 04/05 (4)

- ► 03/22 - 03/29 (4)

- ► 03/15 - 03/22 (1)

- ► 03/08 - 03/15 (8)

- ► 03/01 - 03/08 (6)

- ► 02/22 - 03/01 (6)

- ► 02/15 - 02/22 (1)

- ► 02/08 - 02/15 (3)

- ► 02/01 - 02/08 (3)

- ► 01/25 - 02/01 (8)

- ► 01/18 - 01/25 (7)

- ► 01/11 - 01/18 (7)

- ► 01/04 - 01/11 (3)

-

►

2014

(270)

- ► 12/28 - 01/04 (5)

- ► 12/21 - 12/28 (6)

- ► 12/14 - 12/21 (9)

- ► 12/07 - 12/14 (11)

- ► 11/30 - 12/07 (4)

- ► 11/23 - 11/30 (9)

- ► 11/16 - 11/23 (10)

- ► 11/09 - 11/16 (5)

- ► 11/02 - 11/09 (3)

- ► 10/26 - 11/02 (3)

- ► 10/19 - 10/26 (4)

- ► 10/12 - 10/19 (6)

- ► 10/05 - 10/12 (6)

- ► 09/28 - 10/05 (4)

- ► 09/21 - 09/28 (5)

- ► 09/07 - 09/14 (3)

- ► 08/31 - 09/07 (8)

- ► 08/24 - 08/31 (3)

- ► 08/17 - 08/24 (3)

- ► 08/10 - 08/17 (6)

- ► 08/03 - 08/10 (4)

- ► 07/27 - 08/03 (1)

- ► 07/20 - 07/27 (2)

- ► 07/13 - 07/20 (1)

- ► 07/06 - 07/13 (8)

- ► 06/29 - 07/06 (4)

- ► 06/22 - 06/29 (6)

- ► 06/15 - 06/22 (2)

- ► 06/08 - 06/15 (4)

- ► 06/01 - 06/08 (7)

- ► 05/25 - 06/01 (5)

- ► 05/18 - 05/25 (6)

- ► 05/11 - 05/18 (7)

- ► 05/04 - 05/11 (7)

- ► 04/27 - 05/04 (9)

- ► 04/20 - 04/27 (3)

- ► 04/13 - 04/20 (4)

- ► 04/06 - 04/13 (7)

- ► 03/30 - 04/06 (2)

- ► 03/23 - 03/30 (8)

- ► 03/16 - 03/23 (6)

- ► 03/09 - 03/16 (8)

- ► 03/02 - 03/09 (4)

- ► 02/23 - 03/02 (5)

- ► 02/16 - 02/23 (4)

- ► 02/09 - 02/16 (3)

- ► 02/02 - 02/09 (8)

- ► 01/26 - 02/02 (11)

- ► 01/19 - 01/26 (2)

- ► 01/12 - 01/19 (6)

- ► 01/05 - 01/12 (3)

-

▼

2013

(278)

- ► 12/29 - 01/05 (7)

- ► 12/22 - 12/29 (2)

- ► 12/15 - 12/22 (9)

- ► 12/08 - 12/15 (10)

- ► 12/01 - 12/08 (3)

- ► 11/24 - 12/01 (10)

- ► 11/17 - 11/24 (7)

- ► 11/10 - 11/17 (3)

- ► 11/03 - 11/10 (5)

- ► 10/27 - 11/03 (5)

- ► 10/20 - 10/27 (3)

- ► 10/13 - 10/20 (6)

- ► 10/06 - 10/13 (6)

- ► 09/29 - 10/06 (5)

- ▼ 09/22 - 09/29 (6)

- ► 09/15 - 09/22 (1)

- ► 09/08 - 09/15 (4)

- ► 09/01 - 09/08 (7)

- ► 08/25 - 09/01 (9)

- ► 08/18 - 08/25 (4)

- ► 08/11 - 08/18 (6)

- ► 08/04 - 08/11 (3)

- ► 07/28 - 08/04 (8)

- ► 07/21 - 07/28 (5)

- ► 07/14 - 07/21 (3)

- ► 07/07 - 07/14 (8)

- ► 06/30 - 07/07 (8)

- ► 06/23 - 06/30 (2)

- ► 06/16 - 06/23 (7)

- ► 06/09 - 06/16 (6)

- ► 06/02 - 06/09 (3)

- ► 05/26 - 06/02 (5)

- ► 05/19 - 05/26 (3)

- ► 05/12 - 05/19 (5)

- ► 05/05 - 05/12 (4)

- ► 04/28 - 05/05 (6)

- ► 04/21 - 04/28 (5)

- ► 04/14 - 04/21 (7)

- ► 04/07 - 04/14 (7)

- ► 03/31 - 04/07 (3)

- ► 03/17 - 03/24 (1)

- ► 03/10 - 03/17 (7)

- ► 03/03 - 03/10 (5)

- ► 02/24 - 03/03 (5)

- ► 02/17 - 02/24 (6)

- ► 02/10 - 02/17 (11)

- ► 02/03 - 02/10 (12)

- ► 01/27 - 02/03 (4)

- ► 01/20 - 01/27 (5)

- ► 01/13 - 01/20 (3)

- ► 01/06 - 01/13 (3)

-

►

2012

(303)

- ► 12/30 - 01/06 (2)

- ► 12/23 - 12/30 (3)

- ► 12/16 - 12/23 (6)

- ► 12/09 - 12/16 (2)

- ► 12/02 - 12/09 (17)

- ► 11/25 - 12/02 (2)

- ► 11/18 - 11/25 (3)

- ► 11/11 - 11/18 (9)

- ► 11/04 - 11/11 (5)

- ► 10/28 - 11/04 (6)

- ► 10/21 - 10/28 (9)

- ► 10/14 - 10/21 (7)

- ► 10/07 - 10/14 (9)

- ► 09/30 - 10/07 (6)

- ► 09/23 - 09/30 (6)

- ► 09/16 - 09/23 (8)

- ► 09/09 - 09/16 (4)

- ► 09/02 - 09/09 (7)

- ► 08/26 - 09/02 (2)

- ► 08/19 - 08/26 (3)

- ► 08/05 - 08/12 (2)

- ► 07/29 - 08/05 (5)

- ► 07/22 - 07/29 (3)

- ► 07/15 - 07/22 (7)

- ► 07/08 - 07/15 (6)

- ► 07/01 - 07/08 (3)

- ► 06/24 - 07/01 (6)

- ► 06/17 - 06/24 (7)

- ► 06/10 - 06/17 (5)

- ► 06/03 - 06/10 (4)

- ► 05/27 - 06/03 (6)

- ► 05/20 - 05/27 (3)

- ► 05/13 - 05/20 (3)

- ► 05/06 - 05/13 (3)

- ► 04/29 - 05/06 (3)

- ► 04/22 - 04/29 (4)

- ► 04/15 - 04/22 (4)

- ► 04/08 - 04/15 (9)

- ► 04/01 - 04/08 (9)

- ► 03/25 - 04/01 (4)

- ► 03/18 - 03/25 (7)

- ► 03/11 - 03/18 (4)

- ► 03/04 - 03/11 (5)

- ► 02/26 - 03/04 (7)

- ► 02/19 - 02/26 (7)

- ► 02/12 - 02/19 (3)

- ► 02/05 - 02/12 (7)

- ► 01/29 - 02/05 (12)

- ► 01/22 - 01/29 (8)

- ► 01/15 - 01/22 (13)

- ► 01/08 - 01/15 (8)

- ► 01/01 - 01/08 (10)

-

►

2011

(446)

- ► 12/25 - 01/01 (12)

- ► 12/18 - 12/25 (12)

- ► 12/11 - 12/18 (14)

- ► 12/04 - 12/11 (11)

- ► 11/27 - 12/04 (13)

- ► 11/20 - 11/27 (17)

- ► 11/13 - 11/20 (19)

- ► 11/06 - 11/13 (12)

- ► 10/30 - 11/06 (10)

- ► 10/23 - 10/30 (22)

- ► 10/16 - 10/23 (5)

- ► 10/09 - 10/16 (7)

- ► 10/02 - 10/09 (8)

- ► 09/25 - 10/02 (7)

- ► 09/18 - 09/25 (9)

- ► 09/11 - 09/18 (5)

- ► 09/04 - 09/11 (4)

- ► 08/28 - 09/04 (7)

- ► 08/21 - 08/28 (8)

- ► 08/14 - 08/21 (8)

- ► 08/07 - 08/14 (8)

- ► 07/31 - 08/07 (11)

- ► 07/24 - 07/31 (7)

- ► 07/17 - 07/24 (8)

- ► 07/10 - 07/17 (9)

- ► 07/03 - 07/10 (12)

- ► 06/26 - 07/03 (9)

- ► 06/19 - 06/26 (14)

- ► 06/12 - 06/19 (11)

- ► 06/05 - 06/12 (10)

- ► 05/29 - 06/05 (10)

- ► 05/22 - 05/29 (10)

- ► 05/15 - 05/22 (11)

- ► 05/08 - 05/15 (3)

- ► 05/01 - 05/08 (8)

- ► 04/24 - 05/01 (4)

- ► 04/17 - 04/24 (5)

- ► 04/10 - 04/17 (5)

- ► 04/03 - 04/10 (9)

- ► 03/27 - 04/03 (2)

- ► 03/20 - 03/27 (3)

- ► 03/13 - 03/20 (4)

- ► 03/06 - 03/13 (11)

- ► 02/27 - 03/06 (7)

- ► 02/20 - 02/27 (10)

- ► 02/13 - 02/20 (6)

- ► 01/30 - 02/06 (1)

- ► 01/23 - 01/30 (8)

- ► 01/16 - 01/23 (4)

- ► 01/09 - 01/16 (3)

- ► 01/02 - 01/09 (13)

-

►

2010

(196)

- ► 12/26 - 01/02 (6)

- ► 12/19 - 12/26 (7)

- ► 12/12 - 12/19 (7)

- ► 12/05 - 12/12 (14)

- ► 11/28 - 12/05 (3)

- ► 11/21 - 11/28 (6)

- ► 11/14 - 11/21 (8)

- ► 11/07 - 11/14 (3)

- ► 10/31 - 11/07 (4)

- ► 10/17 - 10/24 (2)

- ► 10/10 - 10/17 (3)

- ► 10/03 - 10/10 (3)

- ► 09/26 - 10/03 (1)

- ► 09/19 - 09/26 (4)

- ► 09/12 - 09/19 (2)

- ► 09/05 - 09/12 (8)

- ► 08/29 - 09/05 (2)

- ► 08/22 - 08/29 (4)

- ► 08/15 - 08/22 (8)

- ► 08/08 - 08/15 (2)

- ► 08/01 - 08/08 (1)

- ► 07/25 - 08/01 (8)

- ► 07/18 - 07/25 (5)

- ► 07/11 - 07/18 (10)

- ► 07/04 - 07/11 (4)

- ► 06/27 - 07/04 (7)

- ► 06/20 - 06/27 (4)

- ► 06/13 - 06/20 (3)

- ► 05/30 - 06/06 (1)

- ► 05/23 - 05/30 (5)

- ► 05/16 - 05/23 (3)

- ► 05/09 - 05/16 (6)

- ► 05/02 - 05/09 (7)

- ► 04/25 - 05/02 (2)

- ► 04/18 - 04/25 (4)

- ► 04/11 - 04/18 (3)

- ► 04/04 - 04/11 (1)

- ► 03/28 - 04/04 (2)

- ► 03/14 - 03/21 (2)

- ► 02/28 - 03/07 (1)

- ► 02/21 - 02/28 (2)

- ► 02/14 - 02/21 (12)

- ► 02/07 - 02/14 (1)

- ► 01/31 - 02/07 (4)

- ► 01/17 - 01/24 (1)

-

►

2009

(98)

- ► 12/20 - 12/27 (1)

- ► 12/13 - 12/20 (2)

- ► 12/06 - 12/13 (1)

- ► 11/22 - 11/29 (3)

- ► 11/15 - 11/22 (1)

- ► 11/08 - 11/15 (1)

- ► 11/01 - 11/08 (1)

- ► 10/25 - 11/01 (7)

- ► 10/18 - 10/25 (1)

- ► 10/04 - 10/11 (1)

- ► 09/27 - 10/04 (2)

- ► 09/20 - 09/27 (1)

- ► 09/13 - 09/20 (4)

- ► 09/06 - 09/13 (3)

- ► 08/30 - 09/06 (3)

- ► 08/23 - 08/30 (1)

- ► 08/09 - 08/16 (2)

- ► 08/02 - 08/09 (1)

- ► 07/26 - 08/02 (1)

- ► 06/28 - 07/05 (6)

- ► 06/21 - 06/28 (12)

- ► 06/14 - 06/21 (43)