This is a blog about the Bronte Sisters, Charlotte, Emily and Anne. And their father Patrick, their mother Maria and their brother Branwell. About their pets, their friends, the parsonage (their house), Haworth the town in which they lived, the moors they loved so much, the Victorian era in which they lived.

I've dreamt in my life dreams that have stayed with me ever after, and changed my ideas: they've gone through and through me, like wine through water, and altered the color of my mind.

Emily BronteWuthering Heights

zaterdag 12 maart 2011

LINKS TO VICTORIAN RESOURCES ONLINE ( As a treasure chest for me).

I was looking for information about womenwriters and found this very interesting:

LINKS TO VICTORIAN RESOURCES ONLINE

For instance I found this

- http://jco.usfca.edu/text/eyre.html Jane Eyre: An Introduction

- http://faculty.plattsburgh.edu/ Jane Eyre: Quarterly Review (December 1848)

- http://www.lang.nagoya-u.ac.jp/~matsuoka/Bronte.html O Brontë Sisters within my Breast !

What a lot of information.

Through http://www.bl.uk/pointsofview/ the 19th century in photographes,

I found

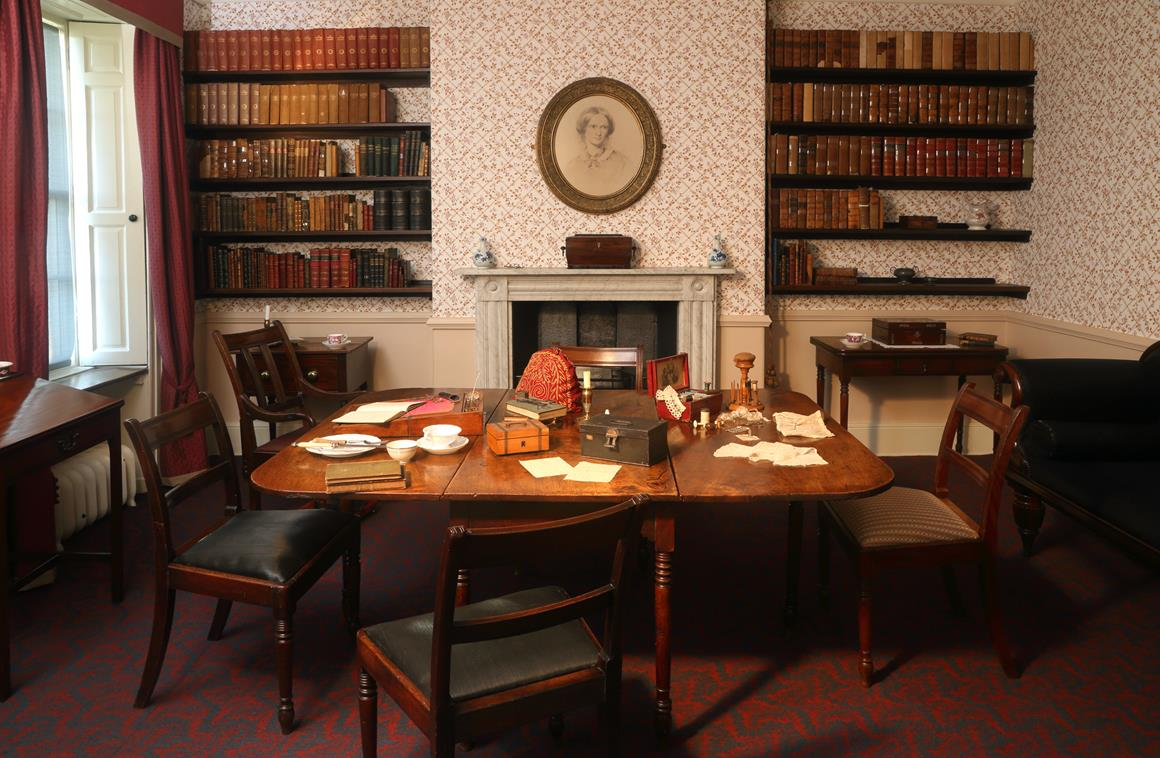

Sisters Charlotte, Emily, Anne and their brother Branwell used the table from childhood and Wuthering Heights, Jane Eyre and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall were amongst the works produced on it.

Made from Cuban mahogany on an oak base, the table is a real writer's work-place, stained with ink spills and scarred in the centre with a large candle burn. At one end a bold letter E is carved into the surface, almost certainly the work of young Emily, whose initial can also be seen in the notebook of her poems that will be displayed on the table.

Each night after their father retired to bed, the sisters would walk around the table and discuss their writing. After the early deaths of her brother and sisters, Charlotte was unable to break the habit and sadly continued the nightly routine on her own.The table is in private ownership; it was purchased at the sale of the household effects of the parsonage after the death of Reverend Brontë in 1861 and was sold soon afterwards to the family in whose possession it has since remained. It has only once been seen outside the family when it was lent to the Brontë museum at Haworth for a short period.

Literature cannot be the business of a woman's life

Charlotte Bronte wrote in her- The History of the Year

""I am in the Kitchen of the Parsonage house Haworth.

Tabby the servant is washing up after breakfast

and Anne my youngest sister

is kneeling on a chair

looking at some cakes which Tabby has been baking for us.

Emily is in the parlour brushing it,

Papa and Branwell are gone to Keighley.

Aunt is up stairs in her room

and I am sitting by the table writing this in the kitchen."

-------------------------------

The same day

The same day

in 12-03-1829

Charlotte Bronte received a letter from Robert Southey

The Poet Laureate:

(In December 1836 twenty-year-old Charlotte Brontë

wrote to Southey

asking his opinion of some verses she sent him.)

(In December 1836 twenty-year-old Charlotte Brontë

wrote to Southey

asking his opinion of some verses she sent him.)

"Literature cannot be the business of a woman's life:

& it ought not to be.

The more she is engaged in her proper duties,

the less leisure she will have for it,

even as an accomplishment & a recreation.

To those duties you have not yet been called,

& when you are you will be less eager for celebrity".

Charlotte reply was humble:

"I trust I shall never more feel ambitious to see my name in print;

if the wish should rise,

I'll look at Southey's letter,

and suppress it."

donderdag 10 maart 2011

Ellen Nussey

http://24corners.blogspot.com/ said:

Isn't it interesting that Ellen said "in faith to his wife's wishes", as if Charlotte had wished Ellen to receive back all her letters...this seems mysterious! I can't imagine that Charlotte would have burned the letters...she was in the habit of keeping such things so dear to her...very curious!

I have a lot of questions as well.

I found this Reminiscences of Charlotte Bronte from Ellen Nussey.

http://books.google.nl/

http://www.gutenberg.org/

Isn't it interesting that Ellen said "in faith to his wife's wishes", as if Charlotte had wished Ellen to receive back all her letters...this seems mysterious! I can't imagine that Charlotte would have burned the letters...she was in the habit of keeping such things so dear to her...very curious!

I have a lot of questions as well.

- Ellen was worried about Charlotte when she was ill. She wrote letters. But A.B. Nicolls said: in fact I cannot remember having ever seen a scrap of her handwriting.

- Charlotte kept the letters of Mary. Why not letters of Ellen?

I started to be curieus about the sources we have from Ellen.

I found this Reminiscences of Charlotte Bronte from Ellen Nussey.

http://books.google.nl/

http://www.gutenberg.org/

woensdag 9 maart 2011

Letters of Ellen Nussey to Charlotte Bronte.

In the fully revised and updated book The Brontes from Juliet Parker I found this information about the Letters of Ellen Nussey.

CB to EN 7 nov.1854: as to my own notes, I never thougt of attaching importance to them, or considering their fate- till Arthus seemed to reflect on both so seriously. http://greeneyedmystic.blogspot.com/2010/09/charlotte-bronte-letters-1853-55.html

A sharp exchange, through Clement Shorter, over 40 years later, revealed the fact that Charlotte had not kept Ellen's letters.

EN to Clement Shorter 10-04-1895 ""Pray to mr. Nicholls that if he has found letters written by me to Charlotte before marriage, that I request that in faith to his wifes wishes he will seal them to me at once""- She declared her intention of destroying everything of the kind.

ABN to Clement Shorter 26-04-1895: You may tell Miss Nussey that her letters never came into my possession; in fact I cannot remember having ever seen a scrap of her handwriting. I presume my wife burned them as soon as read.

Who is Clement Shorter?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clement_King_Shorter

The story of how Arthur Nicholls was persuaded to part with his treasured mementos

And by whom, has itself been the subject of books, but the bones of the story are this: on the 31 July 1895, the fortieth anniversary of Charlotte’s death, Arthur Nicholls received a visit from Clement Shorter, a book collector and journalist on the Illustrated London News who had written an introduction to one of the cheap editions of Jane Eyre. Shorter was researching a new biography of Charlotte that was to come out the following year underthe title Charlotte Brontë and her Circle (1896), and he interviewed Nicholls at length.

However, during the interview, Shorter managed to persuade Nicholls to part with the

greater part of his manuscripts and letters, including the little books. Shorter told Nicholls that close study of the juvenilia would cast valuable new light on the Brontës’literary development, and he promised that, when he had finished with the manuscripts, they would be deposited in the safe keeping of the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington. Nicholls was, by 1895, seventy-six years old, and the promise of his treasures being secured for the nation rather than cast, after his death, upon the market,

evidently appealed to him, as too would the money, for his means were by thenstraightened. He sold the collection, with exclusive rights, to Clement Shorter. But Shorter was not working alone in the purchase of Nicholls’ collection, he had a partner in the London bibliographer and book dealer, T. J. Wise, and Nicholls received cheques from both of them. Over the years that followed, most of the Brontës’ early

poems and stories were first published (under Shorter’s assumed copyright) by either Shorter or Wise, but none of the manuscripts ever saw the inside of the South

Kensington Museum. Wise vandalized Nicholls’ collection and sold it, scattering it across the globe.

http://brontesisterslinks.tripod.com/Bonnell.pdf

CB to EN 7 nov.1854: as to my own notes, I never thougt of attaching importance to them, or considering their fate- till Arthus seemed to reflect on both so seriously. http://greeneyedmystic.blogspot.com/2010/09/charlotte-bronte-letters-1853-55.html

A sharp exchange, through Clement Shorter, over 40 years later, revealed the fact that Charlotte had not kept Ellen's letters.

EN to Clement Shorter 10-04-1895 ""Pray to mr. Nicholls that if he has found letters written by me to Charlotte before marriage, that I request that in faith to his wifes wishes he will seal them to me at once""- She declared her intention of destroying everything of the kind.

ABN to Clement Shorter 26-04-1895: You may tell Miss Nussey that her letters never came into my possession; in fact I cannot remember having ever seen a scrap of her handwriting. I presume my wife burned them as soon as read.

Who is Clement Shorter?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clement_King_Shorter

The story of how Arthur Nicholls was persuaded to part with his treasured mementos

And by whom, has itself been the subject of books, but the bones of the story are this: on the 31 July 1895, the fortieth anniversary of Charlotte’s death, Arthur Nicholls received a visit from Clement Shorter, a book collector and journalist on the Illustrated London News who had written an introduction to one of the cheap editions of Jane Eyre. Shorter was researching a new biography of Charlotte that was to come out the following year underthe title Charlotte Brontë and her Circle (1896), and he interviewed Nicholls at length.

However, during the interview, Shorter managed to persuade Nicholls to part with the

greater part of his manuscripts and letters, including the little books. Shorter told Nicholls that close study of the juvenilia would cast valuable new light on the Brontës’literary development, and he promised that, when he had finished with the manuscripts, they would be deposited in the safe keeping of the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington. Nicholls was, by 1895, seventy-six years old, and the promise of his treasures being secured for the nation rather than cast, after his death, upon the market,

evidently appealed to him, as too would the money, for his means were by thenstraightened. He sold the collection, with exclusive rights, to Clement Shorter. But Shorter was not working alone in the purchase of Nicholls’ collection, he had a partner in the London bibliographer and book dealer, T. J. Wise, and Nicholls received cheques from both of them. Over the years that followed, most of the Brontës’ early

poems and stories were first published (under Shorter’s assumed copyright) by either Shorter or Wise, but none of the manuscripts ever saw the inside of the South

Kensington Museum. Wise vandalized Nicholls’ collection and sold it, scattering it across the globe.

http://brontesisterslinks.tripod.com/Bonnell.pdf

dinsdag 8 maart 2011

Search for the letters of Ellen Nussey.

24 Corners makes me aware that the book: ""Letters to Charlotte"" consist fictionalized letters.

My search to the letters from Ellen to Charlotte continues.

I was looking allready in the books of Rebecca West and Juliette Parker, but till now I didn't read anything about it.

Here you can read an interesting review about Letters to Charlotte - A Review

My search to the letters from Ellen to Charlotte continues.

I was looking allready in the books of Rebecca West and Juliette Parker, but till now I didn't read anything about it.

Here you can read an interesting review about Letters to Charlotte - A Review

maandag 7 maart 2011

Letters from Ellen Nussey, where are they?

http://24corners.blogspot.com/ asked me:

Have you ever read any of Ellen's letters to Charlotte? I've only read Charlotte's to her. It would be nice to hear Ellen's voice, as it has been so nice to hear Mary's.

Have you ever read any of Ellen's letters to Charlotte? I've only read Charlotte's to her. It would be nice to hear Ellen's voice, as it has been so nice to hear Mary's.

I like this question and I am looking for an answer.

I found this information about a letter from Charlotte, it is not about the topic, but still interesting.

A letter by Charlotte Brontë found in a laundry room

Over 350 letters from Charlotte Brontë to Nussey were used in Gaskell's The Life of Charlotte Brontë he prevented at least one other publication from using them. Following Nussey's death in 1897, aged 80, her possessions and letters were dispersed at auction, and many of Brontë's letters to her eventually made their way through donation or purchase to the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth in Yorkshire.

Catalogue of letters

http://www.ampltd.co.uk/collections

(This is interesting, doesn't have to do with the letters I am searching for.

http://www.spring.net/ )

Ellen Nussey, visiting Haworth for the first time some twenty years earlier, also found the Parsonage scrupulously clean but considerably more austere. There were no curtains at the windows because, she said, of Patrick's fear of fire though internal wooden shutters more than adequately supplied their place.

'There was not much carpet any where except in the Sitting room, and on the centre of the study floor. The hall floor and stairs were done with sand stone, always beautifully clean as everything about the house was, the walls were not papered but coloured in a pretty dove-coloured tint, hair-seated chairs and mahogany tables, book-shelves in the Study but not many of these elsewhere. Scant and bare indeed many will say, yet it was not a scantness that made itself felt . . .'

In 1871, Ellen Nussey, a lifelong friend of the Brontës, wrote of her first impressions of the fifteen-year-old Emily in Reminiscences of Charlotte Brontë:

Emily Brontë had by this time acquired a lithesome, graceful figure. She was the tallest person in the house, except her father. Her hair, which was naturally as beautiful as Charlotte's, was in the same unbecoming tight curl and frizz, and there was the same want of complexion. She had very beautiful eyes – kind, kindling, liquid eyes; but she did not often look at you; she was too reserved. Their colour might be said to be dark grey, at other times dark blue, they varied so. She talked very little. She and Anne were like twins – inseparable companions, and in the very closest sympathy, which never had any interruption.

http://www.wuthering-heights.co.uk/emily.htm

Have you ever read any of Ellen's letters to Charlotte? I've only read Charlotte's to her. It would be nice to hear Ellen's voice, as it has been so nice to hear Mary's.

Have you ever read any of Ellen's letters to Charlotte? I've only read Charlotte's to her. It would be nice to hear Ellen's voice, as it has been so nice to hear Mary's.I like this question and I am looking for an answer.

I found this information about a letter from Charlotte, it is not about the topic, but still interesting.

A letter by Charlotte Brontë found in a laundry room

This book is about Ellens' letters, but now ....

are Ellen's letters on internet?

Over 350 letters from Charlotte Brontë to Nussey were used in Gaskell's The Life of Charlotte Brontë he prevented at least one other publication from using them. Following Nussey's death in 1897, aged 80, her possessions and letters were dispersed at auction, and many of Brontë's letters to her eventually made their way through donation or purchase to the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth in Yorkshire.

Catalogue of letters

http://www.ampltd.co.uk/collections

(This is interesting, doesn't have to do with the letters I am searching for.

http://www.spring.net/ )

Ellen Nussey, visiting Haworth for the first time some twenty years earlier, also found the Parsonage scrupulously clean but considerably more austere. There were no curtains at the windows because, she said, of Patrick's fear of fire though internal wooden shutters more than adequately supplied their place.

'There was not much carpet any where except in the Sitting room, and on the centre of the study floor. The hall floor and stairs were done with sand stone, always beautifully clean as everything about the house was, the walls were not papered but coloured in a pretty dove-coloured tint, hair-seated chairs and mahogany tables, book-shelves in the Study but not many of these elsewhere. Scant and bare indeed many will say, yet it was not a scantness that made itself felt . . .'

In 1871, Ellen Nussey, a lifelong friend of the Brontës, wrote of her first impressions of the fifteen-year-old Emily in Reminiscences of Charlotte Brontë:

Emily Brontë had by this time acquired a lithesome, graceful figure. She was the tallest person in the house, except her father. Her hair, which was naturally as beautiful as Charlotte's, was in the same unbecoming tight curl and frizz, and there was the same want of complexion. She had very beautiful eyes – kind, kindling, liquid eyes; but she did not often look at you; she was too reserved. Their colour might be said to be dark grey, at other times dark blue, they varied so. She talked very little. She and Anne were like twins – inseparable companions, and in the very closest sympathy, which never had any interruption.

http://www.wuthering-heights.co.uk/emily.htm

CONCLUSION:

I only find letters from Charlotte to Ellen,

but no letters of Ellen to Charlotte

but no letters of Ellen to Charlotte

I read on an website that non of the letters of Ellen exists anymore.

When I go to this website again I am not allowed anymore.

What I did read was:

Presumably they were destroyed just as Nussey was asked by Brontë’s husband Arthur Bell, soon after their marriage, to destroy those she had received from Brontë because of their ‘passionate language’. She refused.

A surviving letter from Charlotte to Ellen dated 20 october 1854 shows her husband’s surveillance in action:

A surviving letter from Charlotte to Ellen dated 20 october 1854 shows her husband’s surveillance in action:

Arthur has just been glancing over this note . . . you must BURN it when read. Arthur says such letters as mine never ought to be kept, they are dangerous as Lucifer matches so be sure to follow the recommendation he has just given, ‘fire them’ or ‘there will be no more,’ such is his resolve . . . he is bending over the desk with his eyes full of concern. I am now desired to have done with it . . .

The writer of the book Letters tot Charlotte Caeia March keeps an weblog, she writes:

The next day I had a small an intimate reading in a friend’s home – a warm and friendly gathering in which I was asked: Why do you think that Ellen Nussey chose not to burn her letters? This I shall answer more fully in an Ezine article soon. Here I would comment that I am certain she kept them as an embodiment of the Charlotte whom she had loved so deeply and for all of her own life. Ellen did not die until she was over eighty, in the November of 1897. I think she would have read and reread Charlotte’s hand writing, imagining or even feeling Charlotte’s presence though the sight of the formed words and phrases and the shape of the signatures.

What I wonder is: Is this about the letters Charlotte wrote to Ellen, or also about the letters Ellen wrote to Charlotte.

Question: What happened to the letters Ellen Nussey sent to Charlotte Bronte?

zondag 6 maart 2011

Mary Taylor went with her brother to New Zealand. I wonder how she felt?

I am sure she liked the adventure, but in what kind of a country did she arrive? On what kind of a ship did she travel?

I am going to look for some answers.

http://www.britishempire.co.uk/maproom/newzealand.htm

Until 1839 there were only about 2,000 immigrants in New Zealand; by 1852 there were about 28,000. The decisive moment for this remarkable change was 1840. In that year the Treaty of Waitangi was signed. This established British authority in European eyes, and gave British immigrants legal rights as citizens. The treaty helped ensure that for the next century and beyond, most immigrants to New Zealand would come from the United Kingdom.

While many of the early English immigrants came from the south, later in the 19th century they came from the industrial areas in the north, from Yorkshire and Lancashire, and they brought new traditions.

Investors in the The New Zealand Company were promised 100 acres (40.5 hectares) of farmland and one town acre; the initial 1,000 orders were snapped up in a month. But how to attract the labourers? To combat negative notions about New Zealand, the company used books, pamphlets and broadsheets to promote the country as ‘a Britain of the South’, a fertile land with a benign climate, free of starvation, class war and teeming cities. Agents spread the good news around the rural areas of southern England and Scotland. As added inducement the company offered free passages to ‘mechanics, gardeners and agricultural labourers’. Some responded and the first ships arrived in Wellington from January 1840,

By 1843 the new settlers were short of food and the company was virtually bankrupt. Two interventions by the British government saved it from total disaster. Yet the company began to organise large-scale migration to New Zealand. Advertising and propaganda attracted thousands of people over the next 100 years, and the main drawcard, the free or assisted passage, became hugely important. Company immigrants sent letters back home which encouraged others to come out .

http://www.teara.govt.nz/

http://www.britishempire.co.uk/maproom/newzealand.htm

I am going to look for some answers.

http://www.britishempire.co.uk/maproom/newzealand.htm

Until 1839 there were only about 2,000 immigrants in New Zealand; by 1852 there were about 28,000. The decisive moment for this remarkable change was 1840. In that year the Treaty of Waitangi was signed. This established British authority in European eyes, and gave British immigrants legal rights as citizens. The treaty helped ensure that for the next century and beyond, most immigrants to New Zealand would come from the United Kingdom.

While many of the early English immigrants came from the south, later in the 19th century they came from the industrial areas in the north, from Yorkshire and Lancashire, and they brought new traditions.

Investors in the The New Zealand Company were promised 100 acres (40.5 hectares) of farmland and one town acre; the initial 1,000 orders were snapped up in a month. But how to attract the labourers? To combat negative notions about New Zealand, the company used books, pamphlets and broadsheets to promote the country as ‘a Britain of the South’, a fertile land with a benign climate, free of starvation, class war and teeming cities. Agents spread the good news around the rural areas of southern England and Scotland. As added inducement the company offered free passages to ‘mechanics, gardeners and agricultural labourers’. Some responded and the first ships arrived in Wellington from January 1840,

By 1843 the new settlers were short of food and the company was virtually bankrupt. Two interventions by the British government saved it from total disaster. Yet the company began to organise large-scale migration to New Zealand. Advertising and propaganda attracted thousands of people over the next 100 years, and the main drawcard, the free or assisted passage, became hugely important. Company immigrants sent letters back home which encouraged others to come out .

http://www.teara.govt.nz/

http://www.britishempire.co.uk/maproom/newzealand.htm

-------------------------------

The settler ships http://homepages.ihug.co.nz/~tonyf/first/settlers.html

DID MARY TRAVEL ALONE?

Mary’s brother Waring arrived in 1842. In 1845 Mary sailed for Wellington, New Zealand on the barque ‘Louisa Campbell’ – it was a long and uncomfortable journey of four months.

At first Mary lived with Waring, an importer. She earned money teaching piano, renting out a house she had built and trading livestock. There were shortages of supplies such as clothing and furniture.

The Louisa Campbell.

Two voyages to New Zealand were made by the Louisa Campbell, a barque of 350 tons, in command of Captain Darby. Her first appearance was in 1845. She sailed from Plymouth on March 21, and during a severe gale in the Bay of Biscay was damaged to such an extent that she had to put into St. Jago for repairs, which took five days, but the rest of the voyage was uneventful, and she arrived at Nelson on July 9th, the passage having taken 110 days port to port. After landing some passengers and part cargo, she sailed for Wellington and Auckland, reaching the latter port on August 18th, and landing the rest of her passengers.

-----------------------

THE PIONEER WOMEN

The life and times of the women folk

by Anthony G. Flude ©2001

There were the ''assisted'' passengers aboard the emigrant ships who were quartered in the hold. The family groups were herded together in small cramped conditions among the many other emigrants aboard and left to find their own space among the barrels, ropes and sails.

There were no toilet facilities and so scarlet fever, measles, diphtheria and dysentery attacked many of the families. Other fare paying passengers who were allocated cabins fared much better in their accommodation aboard ship.

In the early settlers kitchen, cooking was done over an open fire. Pots for boiling were suspended on an iron frame from hooks over the heat, while roasting of meat and poultry was done on a clockwork or hand operated roasting spit. Cast iron cooking ranges were not introduced into New Zealand until the 1850's which were fueled by wood or coal and also supplied hot water.

Mary did not have gas and for cooking and lighting till 1862?

The Auckland Gas Works was built in the year 1862, bring a supply of gas for cooking and lighting to Auckland Township houses. By 1869, gas was available to households in Wellington.

The magic of history and internet.

I received this reaction on my blog about the LETTERS:

This was wonderful Geri...I've taken two whole days to properly read all and have learned so much. First off, I had no idea all these letters existed from Mary, I was so surprised. Her take on Shirley was so fun to read as well as her adventures in setting up shop. The tone of her letters compared to Ellen's is much different, more real and sister like. I was glad to read that she regretted burning Charlotte's letters, that somehow satisfied me.

This was wonderful Geri...I've taken two whole days to properly read all and have learned so much. First off, I had no idea all these letters existed from Mary, I was so surprised. Her take on Shirley was so fun to read as well as her adventures in setting up shop. The tone of her letters compared to Ellen's is much different, more real and sister like. I was glad to read that she regretted burning Charlotte's letters, that somehow satisfied me. I know I'll be re-reading this post often, there is so much that is interesting. I didn't know about High Royd and went to it's website, so happy the home is being used and Mary's name and history are still attached to it. If I ever get to have my Bronte dream vacation, I will visit there too!

I had the same reaction. I was so surprised and touched reading it.

It came all so near.

I did only know what I was reading in the books from Juliet Parker and Rebecca West.

And suddenly Mary Taylor became so close to me. The photographs, reading about her shop, seeing Wellington in those days and suddenly these letters..... These women, Charlotte, Mary and Ellen,

their friendship, suddenly it was like it still exists. Letters, fotographs, memories, we can meet them because of internet. It is so wonderful and touching.

I will read it again and again.

I didn't know about High Royd as well, so I was searching for http://www.gomersallodge.co.uk/index.html

Gomersal Lodge Hotel, formerly named High Royd, was built for Mary Taylor on her return from New Zealand in 1860. Mary Taylor (1817 -93) of Red House was famous in no small part because of her friendship with Charlotte Bronte to whom she was an inspiration and driving force.

By seeing this I realise Mary returned to the place where she lived before, to the place of the Red House.

Grotere kaart weergeven

Abonneren op:

Posts (Atom)

The Parlour

Parsonage

Charlotte Bronte

Presently the door opened, and in came a superannuated mastiff, followed by an old gentleman very like Miss Bronte, who shook hands with us, and then went to call his daughter. A long interval, during which we coaxed the old dog, and looked at a picture of Miss Bronte, by Richmond, the solitary ornament of the room, looking strangely out of place on the bare walls, and at the books on the little shelves, most of them evidently the gift of the authors since Miss Bronte's celebrity. Presently she came in, and welcomed us very kindly, and took me upstairs to take off my bonnet, and herself brought me water and towels. The uncarpeted stone stairs and floors, the old drawers propped on wood, were all scrupulously clean and neat. When we went into the parlour again, we began talking very comfortably, when the door opened and Mr. Bronte looked in; seeing his daughter there, I suppose he thought it was all right, and he retreated to his study on the opposite side of the passage; presently emerging again to bring W---- a country newspaper. This was his last appearance till we went. Miss Bronte spoke with the greatest warmth of Miss Martineau, and of the good she had gained from her. Well! we talked about various things; the character of the people, - about her solitude, etc., till she left the room to help about dinner, I suppose, for she did not return for an age. The old dog had vanished; a fat curly-haired dog honoured us with his company for some time, but finally manifested a wish to get out, so we were left alone. At last she returned, followed by the maid and dinner, which made us all more comfortable; and we had some very pleasant conversation, in the midst of which time passed quicker than we supposed, for at last W---- found that it was half-past three, and we had fourteen or fifteen miles before us. So we hurried off, having obtained from her a promise to pay us a visit in the spring... ------------------- "She cannot see well, and does little beside knitting. The way she weakened her eyesight was this: When she was sixteen or seventeen, she wanted much to draw; and she copied nimini-pimini copper-plate engravings out of annuals, ('stippling,' don't the artists call it?) every little point put in, till at the end of six months she had produced an exquisitely faithful copy of the engraving. She wanted to learn to express her ideas by drawing. After she had tried to draw stories, and not succeeded, she took the better mode of writing; but in so small a hand, that it is almost impossible to decipher what she wrote at this time.

I asked her whether she had ever taken opium, as the description given of its effects in Villette was so exactly like what I had experienced, - vivid and exaggerated presence of objects, of which the outlines were indistinct, or lost in golden mist, etc. She replied, that she had never, to her knowledge, taken a grain of it in any shape, but that she had followed the process she always adopted when she had to describe anything which had not fallen within her own experience; she had thought intently on it for many and many a night before falling to sleep, - wondering what it was like, or how it would be, - till at length, sometimes after the progress of her story had been arrested at this one point for weeks, she wakened up in the morning with all clear before her, as if she had in reality gone through the experience, and then could describe it, word for word, as it had happened. I cannot account for this psychologically; I only am sure that it was so, because she said it. ----------------------She thought much of her duty, and had loftier and clearer notions of it than most people, and held fast to them with more success. It was done, it seems to me, with much more difficulty than people have of stronger nerves, and better fortunes. All her life was but labour and pain; and she never threw down the burden for the sake of present pleasure. I don't know what use you can make of all I have said. I have written it with the strong desire to obtain appreciation for her. Yet, what does it matter? She herself appealed to the world's judgement for her use of some of the faculties she had, - not the best, - but still the only ones she could turn to strangers' benefit. They heartily, greedily enjoyed the fruits of her labours, and then found out she was much to be blamed for possessing such faculties. Why ask for a judgement on her from such a world?" elizabeth gaskell/charlotte bronte

I asked her whether she had ever taken opium, as the description given of its effects in Villette was so exactly like what I had experienced, - vivid and exaggerated presence of objects, of which the outlines were indistinct, or lost in golden mist, etc. She replied, that she had never, to her knowledge, taken a grain of it in any shape, but that she had followed the process she always adopted when she had to describe anything which had not fallen within her own experience; she had thought intently on it for many and many a night before falling to sleep, - wondering what it was like, or how it would be, - till at length, sometimes after the progress of her story had been arrested at this one point for weeks, she wakened up in the morning with all clear before her, as if she had in reality gone through the experience, and then could describe it, word for word, as it had happened. I cannot account for this psychologically; I only am sure that it was so, because she said it. ----------------------She thought much of her duty, and had loftier and clearer notions of it than most people, and held fast to them with more success. It was done, it seems to me, with much more difficulty than people have of stronger nerves, and better fortunes. All her life was but labour and pain; and she never threw down the burden for the sake of present pleasure. I don't know what use you can make of all I have said. I have written it with the strong desire to obtain appreciation for her. Yet, what does it matter? She herself appealed to the world's judgement for her use of some of the faculties she had, - not the best, - but still the only ones she could turn to strangers' benefit. They heartily, greedily enjoyed the fruits of her labours, and then found out she was much to be blamed for possessing such faculties. Why ask for a judgement on her from such a world?" elizabeth gaskell/charlotte bronte

Poem: No coward soul is mine

No coward soul is mine,

No trembler in the worlds storm-troubled sphere:

I see Heavens glories shine,

And faith shines equal, arming me from fear.

O God within my breast.

Almighty, ever-present Deity!

Life -- that in me has rest,

As I -- Undying Life -- have power in Thee!

Vain are the thousand creeds

That move mens hearts: unutterably vain;

Worthless as withered weeds,

Or idlest froth amid the boundless main,

To waken doubt in one

Holding so fast by Thine infinity;

So surely anchored on

The steadfast Rock of immortality.

With wide-embracing love

Thy Spirit animates eternal years,

Pervades and broods above,

Changes, sustains, dissolves, creates, and rears.

Though earth and man were gone,

And suns and universes ceased to be,

And Thou wert left alone,

Every existence would exist in Thee.

There is not room for Death,

Nor atom that his might could render void:

Thou -- Thou art Being and Breath,

And what Thou art may never be destroyed.

-- Emily Bronte

No trembler in the worlds storm-troubled sphere:

I see Heavens glories shine,

And faith shines equal, arming me from fear.

O God within my breast.

Almighty, ever-present Deity!

Life -- that in me has rest,

As I -- Undying Life -- have power in Thee!

Vain are the thousand creeds

That move mens hearts: unutterably vain;

Worthless as withered weeds,

Or idlest froth amid the boundless main,

To waken doubt in one

Holding so fast by Thine infinity;

So surely anchored on

The steadfast Rock of immortality.

With wide-embracing love

Thy Spirit animates eternal years,

Pervades and broods above,

Changes, sustains, dissolves, creates, and rears.

Though earth and man were gone,

And suns and universes ceased to be,

And Thou wert left alone,

Every existence would exist in Thee.

There is not room for Death,

Nor atom that his might could render void:

Thou -- Thou art Being and Breath,

And what Thou art may never be destroyed.

-- Emily Bronte

Family tree

The Bronte Family

Grandparents - paternal

Hugh Brunty was born 1755 and died circa 1808. He married Eleanor McClory, known as Alice in 1776.

Grandparents - maternal

Thomas Branwell (born 1746 died 5th April 1808) was married in 1768 to Anne Carne (baptised 27th April 1744 and died 19th December 1809).

Parents

Father was Patrick Bronte, the eldest of 10 children born to Hugh Brunty and Eleanor (Alice) McClory. He was born 17th March 1777 and died on 7th June 1861. Mother was Maria Branwell, who was born on 15th April 1783 and died on 15th September 1821.

Maria had a sister, Elizabeth who was known as Aunt Branwell. She was born in 1776 and died on 29th October 1842.

Patrick Bronte married Maria Branwell on 29th December 1812.

The Bronte Children

Patrick and Maria Bronte had six children.

The first child was Maria, who was born in 1814 and died on 6th June 1825.

The second daughter, Elizabeth was born on 8th February 1815 and died shortly after Maria on 15th June 1825. Charlotte was the third daughter, born on 21st April 1816.

Charlotte married Arthur Bell Nicholls (born 1818) on 29th June 1854. Charlotte died on 31st March 1855. Arthur lived until 2nd December 1906.

The first and only son born to Patrick and Maria was Patrick Branwell, who was born on 26th June 1817 and died on 24th September 1848.

Emily Jane, the fourth daughter was born on 30th July 1818 and died on 19th December 1848.

The sixth and last child was Anne, born on 17th January 1820 who died on 28th May 1849.

Grandparents - paternal

Hugh Brunty was born 1755 and died circa 1808. He married Eleanor McClory, known as Alice in 1776.

Grandparents - maternal

Thomas Branwell (born 1746 died 5th April 1808) was married in 1768 to Anne Carne (baptised 27th April 1744 and died 19th December 1809).

Parents

Father was Patrick Bronte, the eldest of 10 children born to Hugh Brunty and Eleanor (Alice) McClory. He was born 17th March 1777 and died on 7th June 1861. Mother was Maria Branwell, who was born on 15th April 1783 and died on 15th September 1821.

Maria had a sister, Elizabeth who was known as Aunt Branwell. She was born in 1776 and died on 29th October 1842.

Patrick Bronte married Maria Branwell on 29th December 1812.

The Bronte Children

Patrick and Maria Bronte had six children.

The first child was Maria, who was born in 1814 and died on 6th June 1825.

The second daughter, Elizabeth was born on 8th February 1815 and died shortly after Maria on 15th June 1825. Charlotte was the third daughter, born on 21st April 1816.

Charlotte married Arthur Bell Nicholls (born 1818) on 29th June 1854. Charlotte died on 31st March 1855. Arthur lived until 2nd December 1906.

The first and only son born to Patrick and Maria was Patrick Branwell, who was born on 26th June 1817 and died on 24th September 1848.

Emily Jane, the fourth daughter was born on 30th July 1818 and died on 19th December 1848.

The sixth and last child was Anne, born on 17th January 1820 who died on 28th May 1849.

Top Withens in the snow.

Blogarchief

-

►

2024

(10)

- ► 03/17 - 03/24 (1)

- ► 02/18 - 02/25 (1)

- ► 01/21 - 01/28 (5)

- ► 01/14 - 01/21 (1)

- ► 01/07 - 01/14 (2)

-

►

2023

(9)

- ► 11/26 - 12/03 (1)

- ► 11/19 - 11/26 (1)

- ► 07/23 - 07/30 (1)

- ► 05/28 - 06/04 (1)

- ► 05/14 - 05/21 (1)

- ► 05/07 - 05/14 (1)

- ► 04/02 - 04/09 (1)

- ► 03/05 - 03/12 (1)

- ► 02/05 - 02/12 (1)

-

►

2022

(27)

- ► 12/25 - 01/01 (1)

- ► 12/04 - 12/11 (1)

- ► 11/20 - 11/27 (1)

- ► 11/13 - 11/20 (2)

- ► 10/30 - 11/06 (2)

- ► 10/23 - 10/30 (2)

- ► 10/09 - 10/16 (2)

- ► 07/17 - 07/24 (1)

- ► 06/12 - 06/19 (1)

- ► 06/05 - 06/12 (1)

- ► 05/22 - 05/29 (2)

- ► 02/27 - 03/06 (1)

- ► 02/20 - 02/27 (1)

- ► 02/13 - 02/20 (7)

- ► 01/16 - 01/23 (2)

-

►

2021

(47)

- ► 12/19 - 12/26 (1)

- ► 12/12 - 12/19 (1)

- ► 11/28 - 12/05 (1)

- ► 11/21 - 11/28 (2)

- ► 11/14 - 11/21 (1)

- ► 10/31 - 11/07 (2)

- ► 08/15 - 08/22 (1)

- ► 08/08 - 08/15 (1)

- ► 08/01 - 08/08 (1)

- ► 07/25 - 08/01 (1)

- ► 07/18 - 07/25 (1)

- ► 07/11 - 07/18 (1)

- ► 06/20 - 06/27 (3)

- ► 06/13 - 06/20 (2)

- ► 06/06 - 06/13 (3)

- ► 05/30 - 06/06 (7)

- ► 05/23 - 05/30 (8)

- ► 05/02 - 05/09 (2)

- ► 04/18 - 04/25 (4)

- ► 04/11 - 04/18 (1)

- ► 03/28 - 04/04 (2)

- ► 01/03 - 01/10 (1)

-

►

2020

(34)

- ► 12/20 - 12/27 (1)

- ► 12/06 - 12/13 (5)

- ► 11/08 - 11/15 (2)

- ► 11/01 - 11/08 (1)

- ► 10/11 - 10/18 (1)

- ► 10/04 - 10/11 (1)

- ► 09/06 - 09/13 (4)

- ► 08/16 - 08/23 (3)

- ► 08/02 - 08/09 (2)

- ► 07/12 - 07/19 (1)

- ► 07/05 - 07/12 (1)

- ► 06/28 - 07/05 (1)

- ► 04/19 - 04/26 (1)

- ► 03/22 - 03/29 (1)

- ► 02/09 - 02/16 (2)

- ► 01/26 - 02/02 (2)

- ► 01/12 - 01/19 (3)

- ► 01/05 - 01/12 (2)

-

►

2019

(34)

- ► 12/29 - 01/05 (2)

- ► 12/15 - 12/22 (1)

- ► 12/08 - 12/15 (1)

- ► 12/01 - 12/08 (3)

- ► 11/17 - 11/24 (2)

- ► 11/10 - 11/17 (2)

- ► 11/03 - 11/10 (1)

- ► 10/13 - 10/20 (2)

- ► 10/06 - 10/13 (1)

- ► 09/22 - 09/29 (1)

- ► 09/08 - 09/15 (1)

- ► 09/01 - 09/08 (3)

- ► 08/25 - 09/01 (2)

- ► 07/21 - 07/28 (1)

- ► 06/30 - 07/07 (2)

- ► 06/09 - 06/16 (1)

- ► 05/26 - 06/02 (1)

- ► 04/14 - 04/21 (1)

- ► 04/07 - 04/14 (1)

- ► 03/03 - 03/10 (1)

- ► 02/17 - 02/24 (2)

- ► 02/10 - 02/17 (1)

- ► 02/03 - 02/10 (1)

-

►

2018

(82)

- ► 12/30 - 01/06 (2)

- ► 12/23 - 12/30 (4)

- ► 12/16 - 12/23 (2)

- ► 11/25 - 12/02 (1)

- ► 11/18 - 11/25 (2)

- ► 11/11 - 11/18 (3)

- ► 11/04 - 11/11 (1)

- ► 10/28 - 11/04 (3)

- ► 10/21 - 10/28 (3)

- ► 10/07 - 10/14 (4)

- ► 09/23 - 09/30 (1)

- ► 08/26 - 09/02 (1)

- ► 08/19 - 08/26 (1)

- ► 08/05 - 08/12 (1)

- ► 07/29 - 08/05 (8)

- ► 07/22 - 07/29 (6)

- ► 06/24 - 07/01 (2)

- ► 06/17 - 06/24 (2)

- ► 06/10 - 06/17 (4)

- ► 06/03 - 06/10 (5)

- ► 05/27 - 06/03 (3)

- ► 05/20 - 05/27 (1)

- ► 05/13 - 05/20 (1)

- ► 05/06 - 05/13 (1)

- ► 04/29 - 05/06 (1)

- ► 04/22 - 04/29 (1)

- ► 04/15 - 04/22 (1)

- ► 04/08 - 04/15 (2)

- ► 04/01 - 04/08 (1)

- ► 03/25 - 04/01 (1)

- ► 03/18 - 03/25 (3)

- ► 03/11 - 03/18 (2)

- ► 03/04 - 03/11 (2)

- ► 02/11 - 02/18 (2)

- ► 01/14 - 01/21 (4)

-

►

2017

(69)

- ► 12/31 - 01/07 (2)

- ► 12/24 - 12/31 (1)

- ► 12/17 - 12/24 (1)

- ► 12/10 - 12/17 (2)

- ► 12/03 - 12/10 (4)

- ► 11/26 - 12/03 (1)

- ► 11/19 - 11/26 (5)

- ► 11/12 - 11/19 (2)

- ► 10/08 - 10/15 (2)

- ► 10/01 - 10/08 (2)

- ► 09/10 - 09/17 (2)

- ► 08/27 - 09/03 (2)

- ► 07/30 - 08/06 (1)

- ► 07/23 - 07/30 (1)

- ► 07/16 - 07/23 (3)

- ► 07/09 - 07/16 (1)

- ► 06/25 - 07/02 (3)

- ► 06/04 - 06/11 (1)

- ► 05/28 - 06/04 (1)

- ► 05/07 - 05/14 (2)

- ► 04/30 - 05/07 (2)

- ► 04/23 - 04/30 (1)

- ► 04/16 - 04/23 (2)

- ► 04/09 - 04/16 (2)

- ► 04/02 - 04/09 (3)

- ► 03/26 - 04/02 (1)

- ► 03/19 - 03/26 (1)

- ► 03/05 - 03/12 (4)

- ► 02/12 - 02/19 (1)

- ► 02/05 - 02/12 (4)

- ► 01/29 - 02/05 (1)

- ► 01/22 - 01/29 (2)

- ► 01/15 - 01/22 (2)

- ► 01/08 - 01/15 (2)

- ► 01/01 - 01/08 (2)

-

►

2016

(126)

- ► 12/25 - 01/01 (3)

- ► 12/18 - 12/25 (4)

- ► 12/04 - 12/11 (1)

- ► 11/27 - 12/04 (4)

- ► 11/20 - 11/27 (1)

- ► 11/13 - 11/20 (3)

- ► 11/06 - 11/13 (8)

- ► 10/30 - 11/06 (1)

- ► 10/23 - 10/30 (1)

- ► 10/16 - 10/23 (3)

- ► 10/09 - 10/16 (2)

- ► 10/02 - 10/09 (3)

- ► 09/11 - 09/18 (1)

- ► 08/28 - 09/04 (2)

- ► 08/21 - 08/28 (3)

- ► 08/07 - 08/14 (1)

- ► 07/31 - 08/07 (1)

- ► 07/24 - 07/31 (4)

- ► 07/17 - 07/24 (3)

- ► 07/03 - 07/10 (1)

- ► 06/26 - 07/03 (4)

- ► 06/19 - 06/26 (3)

- ► 06/12 - 06/19 (2)

- ► 06/05 - 06/12 (8)

- ► 05/29 - 06/05 (3)

- ► 05/22 - 05/29 (3)

- ► 05/08 - 05/15 (3)

- ► 05/01 - 05/08 (2)

- ► 04/24 - 05/01 (1)

- ► 04/17 - 04/24 (6)

- ► 04/10 - 04/17 (2)

- ► 04/03 - 04/10 (1)

- ► 03/27 - 04/03 (6)

- ► 03/20 - 03/27 (4)

- ► 03/13 - 03/20 (7)

- ► 03/06 - 03/13 (6)

- ► 02/28 - 03/06 (3)

- ► 02/21 - 02/28 (1)

- ► 02/14 - 02/21 (2)

- ► 02/07 - 02/14 (2)

- ► 01/31 - 02/07 (2)

- ► 01/17 - 01/24 (2)

- ► 01/10 - 01/17 (1)

- ► 01/03 - 01/10 (2)

-

►

2015

(192)

- ► 12/27 - 01/03 (4)

- ► 12/20 - 12/27 (4)

- ► 12/13 - 12/20 (6)

- ► 12/06 - 12/13 (3)

- ► 11/29 - 12/06 (1)

- ► 11/22 - 11/29 (4)

- ► 11/15 - 11/22 (4)

- ► 11/08 - 11/15 (8)

- ► 11/01 - 11/08 (2)

- ► 10/25 - 11/01 (4)

- ► 10/18 - 10/25 (2)

- ► 10/11 - 10/18 (2)

- ► 10/04 - 10/11 (2)

- ► 09/27 - 10/04 (4)

- ► 09/20 - 09/27 (3)

- ► 09/13 - 09/20 (2)

- ► 09/06 - 09/13 (2)

- ► 08/30 - 09/06 (3)

- ► 08/23 - 08/30 (1)

- ► 08/16 - 08/23 (4)

- ► 08/09 - 08/16 (2)

- ► 08/02 - 08/09 (4)

- ► 07/26 - 08/02 (5)

- ► 07/19 - 07/26 (2)

- ► 07/12 - 07/19 (3)

- ► 07/05 - 07/12 (1)

- ► 06/21 - 06/28 (1)

- ► 06/14 - 06/21 (10)

- ► 06/07 - 06/14 (2)

- ► 05/31 - 06/07 (6)

- ► 05/24 - 05/31 (4)

- ► 05/17 - 05/24 (2)

- ► 05/10 - 05/17 (2)

- ► 05/03 - 05/10 (4)

- ► 04/26 - 05/03 (5)

- ► 04/19 - 04/26 (7)

- ► 04/12 - 04/19 (3)

- ► 04/05 - 04/12 (3)

- ► 03/29 - 04/05 (4)

- ► 03/22 - 03/29 (4)

- ► 03/15 - 03/22 (1)

- ► 03/08 - 03/15 (8)

- ► 03/01 - 03/08 (6)

- ► 02/22 - 03/01 (6)

- ► 02/15 - 02/22 (1)

- ► 02/08 - 02/15 (3)

- ► 02/01 - 02/08 (3)

- ► 01/25 - 02/01 (8)

- ► 01/18 - 01/25 (7)

- ► 01/11 - 01/18 (7)

- ► 01/04 - 01/11 (3)

-

►

2014

(270)

- ► 12/28 - 01/04 (5)

- ► 12/21 - 12/28 (6)

- ► 12/14 - 12/21 (9)

- ► 12/07 - 12/14 (11)

- ► 11/30 - 12/07 (4)

- ► 11/23 - 11/30 (9)

- ► 11/16 - 11/23 (10)

- ► 11/09 - 11/16 (5)

- ► 11/02 - 11/09 (3)

- ► 10/26 - 11/02 (3)

- ► 10/19 - 10/26 (4)

- ► 10/12 - 10/19 (6)

- ► 10/05 - 10/12 (6)

- ► 09/28 - 10/05 (4)

- ► 09/21 - 09/28 (5)

- ► 09/07 - 09/14 (3)

- ► 08/31 - 09/07 (8)

- ► 08/24 - 08/31 (3)

- ► 08/17 - 08/24 (3)

- ► 08/10 - 08/17 (6)

- ► 08/03 - 08/10 (4)

- ► 07/27 - 08/03 (1)

- ► 07/20 - 07/27 (2)

- ► 07/13 - 07/20 (1)

- ► 07/06 - 07/13 (8)

- ► 06/29 - 07/06 (4)

- ► 06/22 - 06/29 (6)

- ► 06/15 - 06/22 (2)

- ► 06/08 - 06/15 (4)

- ► 06/01 - 06/08 (7)

- ► 05/25 - 06/01 (5)

- ► 05/18 - 05/25 (6)

- ► 05/11 - 05/18 (7)

- ► 05/04 - 05/11 (7)

- ► 04/27 - 05/04 (9)

- ► 04/20 - 04/27 (3)

- ► 04/13 - 04/20 (4)

- ► 04/06 - 04/13 (7)

- ► 03/30 - 04/06 (2)

- ► 03/23 - 03/30 (8)

- ► 03/16 - 03/23 (6)

- ► 03/09 - 03/16 (8)

- ► 03/02 - 03/09 (4)

- ► 02/23 - 03/02 (5)

- ► 02/16 - 02/23 (4)

- ► 02/09 - 02/16 (3)

- ► 02/02 - 02/09 (8)

- ► 01/26 - 02/02 (11)

- ► 01/19 - 01/26 (2)

- ► 01/12 - 01/19 (6)

- ► 01/05 - 01/12 (3)

-

►

2013

(278)

- ► 12/29 - 01/05 (7)

- ► 12/22 - 12/29 (2)

- ► 12/15 - 12/22 (9)

- ► 12/08 - 12/15 (10)

- ► 12/01 - 12/08 (3)

- ► 11/24 - 12/01 (10)

- ► 11/17 - 11/24 (7)

- ► 11/10 - 11/17 (3)

- ► 11/03 - 11/10 (5)

- ► 10/27 - 11/03 (5)

- ► 10/20 - 10/27 (3)

- ► 10/13 - 10/20 (6)

- ► 10/06 - 10/13 (6)

- ► 09/29 - 10/06 (5)

- ► 09/22 - 09/29 (6)

- ► 09/15 - 09/22 (1)

- ► 09/08 - 09/15 (4)

- ► 09/01 - 09/08 (7)

- ► 08/25 - 09/01 (9)

- ► 08/18 - 08/25 (4)

- ► 08/11 - 08/18 (6)

- ► 08/04 - 08/11 (3)

- ► 07/28 - 08/04 (8)

- ► 07/21 - 07/28 (5)

- ► 07/14 - 07/21 (3)

- ► 07/07 - 07/14 (8)

- ► 06/30 - 07/07 (8)

- ► 06/23 - 06/30 (2)

- ► 06/16 - 06/23 (7)

- ► 06/09 - 06/16 (6)

- ► 06/02 - 06/09 (3)

- ► 05/26 - 06/02 (5)

- ► 05/19 - 05/26 (3)

- ► 05/12 - 05/19 (5)

- ► 05/05 - 05/12 (4)

- ► 04/28 - 05/05 (6)

- ► 04/21 - 04/28 (5)

- ► 04/14 - 04/21 (7)

- ► 04/07 - 04/14 (7)

- ► 03/31 - 04/07 (3)

- ► 03/17 - 03/24 (1)

- ► 03/10 - 03/17 (7)

- ► 03/03 - 03/10 (5)

- ► 02/24 - 03/03 (5)

- ► 02/17 - 02/24 (6)

- ► 02/10 - 02/17 (11)

- ► 02/03 - 02/10 (12)

- ► 01/27 - 02/03 (4)

- ► 01/20 - 01/27 (5)

- ► 01/13 - 01/20 (3)

- ► 01/06 - 01/13 (3)

-

►

2012

(303)

- ► 12/30 - 01/06 (2)

- ► 12/23 - 12/30 (3)

- ► 12/16 - 12/23 (6)

- ► 12/09 - 12/16 (2)

- ► 12/02 - 12/09 (17)

- ► 11/25 - 12/02 (2)

- ► 11/18 - 11/25 (3)

- ► 11/11 - 11/18 (9)

- ► 11/04 - 11/11 (5)

- ► 10/28 - 11/04 (6)

- ► 10/21 - 10/28 (9)

- ► 10/14 - 10/21 (7)

- ► 10/07 - 10/14 (9)

- ► 09/30 - 10/07 (6)

- ► 09/23 - 09/30 (6)

- ► 09/16 - 09/23 (8)

- ► 09/09 - 09/16 (4)

- ► 09/02 - 09/09 (7)

- ► 08/26 - 09/02 (2)

- ► 08/19 - 08/26 (3)

- ► 08/05 - 08/12 (2)

- ► 07/29 - 08/05 (5)

- ► 07/22 - 07/29 (3)

- ► 07/15 - 07/22 (7)

- ► 07/08 - 07/15 (6)

- ► 07/01 - 07/08 (3)

- ► 06/24 - 07/01 (6)

- ► 06/17 - 06/24 (7)

- ► 06/10 - 06/17 (5)

- ► 06/03 - 06/10 (4)

- ► 05/27 - 06/03 (6)

- ► 05/20 - 05/27 (3)

- ► 05/13 - 05/20 (3)

- ► 05/06 - 05/13 (3)

- ► 04/29 - 05/06 (3)

- ► 04/22 - 04/29 (4)

- ► 04/15 - 04/22 (4)

- ► 04/08 - 04/15 (9)

- ► 04/01 - 04/08 (9)

- ► 03/25 - 04/01 (4)

- ► 03/18 - 03/25 (7)

- ► 03/11 - 03/18 (4)

- ► 03/04 - 03/11 (5)

- ► 02/26 - 03/04 (7)

- ► 02/19 - 02/26 (7)

- ► 02/12 - 02/19 (3)

- ► 02/05 - 02/12 (7)

- ► 01/29 - 02/05 (12)

- ► 01/22 - 01/29 (8)

- ► 01/15 - 01/22 (13)

- ► 01/08 - 01/15 (8)

- ► 01/01 - 01/08 (10)

-

▼

2011

(446)

- ► 12/25 - 01/01 (12)

- ► 12/18 - 12/25 (12)

- ► 12/11 - 12/18 (14)

- ► 12/04 - 12/11 (11)

- ► 11/27 - 12/04 (13)

- ► 11/20 - 11/27 (17)

- ► 11/13 - 11/20 (19)

- ► 11/06 - 11/13 (12)

- ► 10/30 - 11/06 (10)

- ► 10/23 - 10/30 (22)

- ► 10/16 - 10/23 (5)

- ► 10/09 - 10/16 (7)

- ► 10/02 - 10/09 (8)

- ► 09/25 - 10/02 (7)

- ► 09/18 - 09/25 (9)

- ► 09/11 - 09/18 (5)

- ► 09/04 - 09/11 (4)

- ► 08/28 - 09/04 (7)

- ► 08/21 - 08/28 (8)

- ► 08/14 - 08/21 (8)

- ► 08/07 - 08/14 (8)

- ► 07/31 - 08/07 (11)

- ► 07/24 - 07/31 (7)

- ► 07/17 - 07/24 (8)

- ► 07/10 - 07/17 (9)

- ► 07/03 - 07/10 (12)

- ► 06/26 - 07/03 (9)

- ► 06/19 - 06/26 (14)

- ► 06/12 - 06/19 (11)

- ► 06/05 - 06/12 (10)

- ► 05/29 - 06/05 (10)

- ► 05/22 - 05/29 (10)

- ► 05/15 - 05/22 (11)

- ► 05/08 - 05/15 (3)

- ► 05/01 - 05/08 (8)

- ► 04/24 - 05/01 (4)

- ► 04/17 - 04/24 (5)

- ► 04/10 - 04/17 (5)

- ► 04/03 - 04/10 (9)

- ► 03/27 - 04/03 (2)

- ► 03/20 - 03/27 (3)

- ► 03/13 - 03/20 (4)

-

▼

03/06 - 03/13

(11)

- Haworth

- LINKS TO VICTORIAN RESOURCES ONLINE ( As a treasur...

- Literature cannot be the business of a woman's life

- Tomorrow the new Jane Eyre movie.

- Ellen Nussey

- Juliet Barkers's weblog

- Letters of Ellen Nussey to Charlotte Bronte.

- Search for the letters of Ellen Nussey.

- Letters from Ellen Nussey, where are they?

- Mary Taylor went with her brother to New Zealand. ...

- The magic of history and internet.

- ► 02/27 - 03/06 (7)

- ► 02/20 - 02/27 (10)

- ► 02/13 - 02/20 (6)

- ► 01/30 - 02/06 (1)

- ► 01/23 - 01/30 (8)

- ► 01/16 - 01/23 (4)

- ► 01/09 - 01/16 (3)

- ► 01/02 - 01/09 (13)

-

►

2010

(196)

- ► 12/26 - 01/02 (6)

- ► 12/19 - 12/26 (7)

- ► 12/12 - 12/19 (7)

- ► 12/05 - 12/12 (14)

- ► 11/28 - 12/05 (3)

- ► 11/21 - 11/28 (6)

- ► 11/14 - 11/21 (8)

- ► 11/07 - 11/14 (3)

- ► 10/31 - 11/07 (4)

- ► 10/17 - 10/24 (2)

- ► 10/10 - 10/17 (3)

- ► 10/03 - 10/10 (3)

- ► 09/26 - 10/03 (1)

- ► 09/19 - 09/26 (4)

- ► 09/12 - 09/19 (2)

- ► 09/05 - 09/12 (8)

- ► 08/29 - 09/05 (2)

- ► 08/22 - 08/29 (4)

- ► 08/15 - 08/22 (8)

- ► 08/08 - 08/15 (2)

- ► 08/01 - 08/08 (1)

- ► 07/25 - 08/01 (8)

- ► 07/18 - 07/25 (5)

- ► 07/11 - 07/18 (10)

- ► 07/04 - 07/11 (4)

- ► 06/27 - 07/04 (7)

- ► 06/20 - 06/27 (4)

- ► 06/13 - 06/20 (3)

- ► 05/30 - 06/06 (1)

- ► 05/23 - 05/30 (5)

- ► 05/16 - 05/23 (3)

- ► 05/09 - 05/16 (6)

- ► 05/02 - 05/09 (7)

- ► 04/25 - 05/02 (2)

- ► 04/18 - 04/25 (4)

- ► 04/11 - 04/18 (3)

- ► 04/04 - 04/11 (1)

- ► 03/28 - 04/04 (2)

- ► 03/14 - 03/21 (2)

- ► 02/28 - 03/07 (1)

- ► 02/21 - 02/28 (2)

- ► 02/14 - 02/21 (12)

- ► 02/07 - 02/14 (1)

- ► 01/31 - 02/07 (4)

- ► 01/17 - 01/24 (1)

-

►

2009

(98)

- ► 12/20 - 12/27 (1)

- ► 12/13 - 12/20 (2)

- ► 12/06 - 12/13 (1)

- ► 11/22 - 11/29 (3)

- ► 11/15 - 11/22 (1)

- ► 11/08 - 11/15 (1)

- ► 11/01 - 11/08 (1)

- ► 10/25 - 11/01 (7)

- ► 10/18 - 10/25 (1)

- ► 10/04 - 10/11 (1)

- ► 09/27 - 10/04 (2)

- ► 09/20 - 09/27 (1)

- ► 09/13 - 09/20 (4)

- ► 09/06 - 09/13 (3)

- ► 08/30 - 09/06 (3)

- ► 08/23 - 08/30 (1)

- ► 08/09 - 08/16 (2)

- ► 08/02 - 08/09 (1)

- ► 07/26 - 08/02 (1)

- ► 06/28 - 07/05 (6)

- ► 06/21 - 06/28 (12)

- ► 06/14 - 06/21 (43)