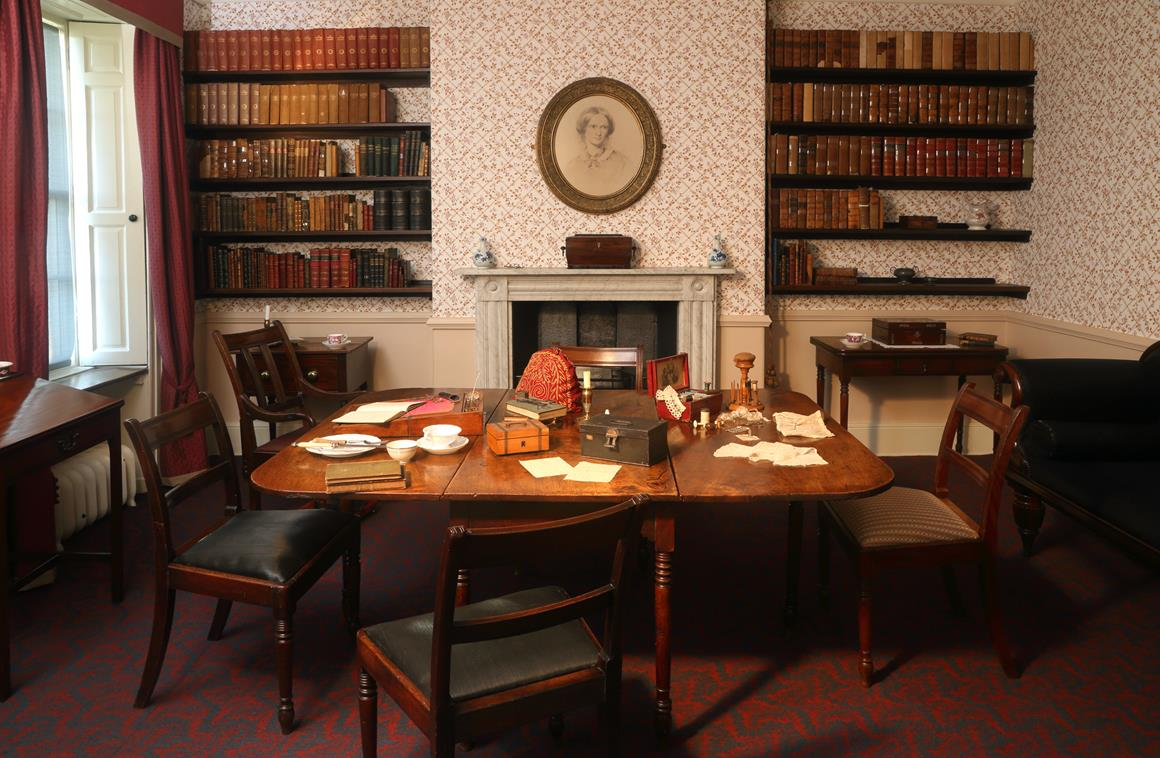

65, Cornhill, London - the premises of Smith, Elder & Co. - Charlotte's publishers. It was into this building where she and Anne walked on Saturday, 8 July 1848, and shocked George Smith (who had already published Jane Eyre, but had never met its author) by presenting him with his own letter that he had addressed to 'Currer Bell': it took him several moments to realise that standing in front of him were Currer and Acton Bell - authors of Jane Eyre and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

On Internet I found this picture

65 Cornhill EC3 (E I'Anson, completed 1870), City of London. Formerly a trading house, now the Shanghai Commerical Bank.

Is this the same building????

Smith, Elder was a London publishing firm noted for its association with many of the foremost writers of the day, including the Brontes, Ruskin, and Thackeray. Founded by George Smith (1789-1846) and Alexander Elder (c. 1790-1876), the firm began as booksellers and stationers in Fenchurch Street, moving to 65 Cornhill in 1824. It was also involved in agency and banking with a strong Indian connection. In 1833, Smith, Elder started 'The Library of Romance', original works in one volume at 6s, the first of a number of attempts by publishers to reduce the price of fiction, already dictated by the circulating libraries.

George Smith

William Smith Williams

George Smith II (1824-1901) became sole head of the firm in 1846, moving to Waterloo Place in 1869. He was renowned as an honourable, hardworking and astute businessman, backing his judgement by offering authors generous payments. Smith founded the Cornhill in 1860, the Pall Mall Gazette in 1865 and launched the Dictionary of National Biography in 1882. The firm was absorbed by John Murray in 1916.

Collins was first introduced to Smith by Ruskin, with a view to publishing Antonina. Smith declined, not wanting a classical novel, but issued After Dark in 1856. Smith always regretted missing The Woman in White. After a few instalments of the serial, in January 1860, Collins received an offer from Sampson Low. He had promised Smith the opportunity of bidding for the book and wrote to him accordingly. Smith asked his clerks but none of them was familiar with the serial. He therefore dictated a hasty note offering a modest £500 and rushed off to a dinner party where he learned that everyone was raving about The Woman in White. He subsequently claimed that had he known this he would have multiplied his offer fivefold.

Smith was also unsuccessful in obtaining No Name, succeeding only in pushing up the price paid by Low to £3,000. Still determined to publish Collins, he secured Armadale for The Cornhill with an offer of £5,000, the largest sum at that time paid to any novelist except Dickens. Smith, Elder also published for Collins the dramatic version of Armadale (1866) in an edition of twenty-five copies.

From 1865, Smith, Elder added to After Dark the seven copyrights previously held by Sampson Low. Until the mid 1870s, Smith, Elder issued various one volume editions which included Armadale and, from 1871, The Moonstone. Smith at this time declined Collins's proposal for cheap reissues. In 1875, therefore, the copyright to most of his earlier works was transferred to Chatto & Windus. There was some period of overlap since Smith, Elder yellowbacks dated 1876 continued to advertise their editions although Chatto & Windus had already issued thirteen titles by July 1875. Smith, Elder retained Armadale, After Dark and No Name and continued to issue them throughout the 1880s. They were not published by Chatto & Windus until 1890.

Lee, Sir Sidney, 'Memoir of George Smith' in Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford; reprinted in George Smith: a Memoir with Some Pages of Autiobiography, for private circulation, London 1902.

Een kranten artikel/ a newspaper story

______________________________________

Document Information: Title: George Smith: publisher

Author(s): Eric Glasgow, (Eric Glasgow is a Retired University Teacher, Southport, Merseyside, UK.)

Citation: Eric Glasgow, (1999) "George Smith: publisher", Library Review, Vol. 48 Iss: 6, pp.290 - 298

Keywords: Books, History, Literature, Publishing, UK

Article type: Research paper

DOI: 10.1108/00242539910283813 (Permanent URL)

Publisher: MCB UP Ltd

Abstract: This is a brief study of the character, and the professional career, of one of the most spectacular and prolific of all the huge medley of book-publishers in Victorian London. George Smith is perhaps today somewhat overshadowed by other famous names. Nevertheless, in 1944, the Cambridge historian, G.M. Trevelyan, singled him from the rest: as the publisher of the monumental Dictionary of National Biography. As the nineteenth century’s cult of printed books inevitably now recedes in favour of information technology, perhaps the time is ripe for this succinct evaluation of an extraordinary publisher from Victorian times who promoted not only works by Leslie Stephen, Thackeray, and many other literary men but particularly works by women-novelists, such as Charlotte Bronte and Elizabeth Gaskell, despite the fact that he was far from being a “feminist”, in our own contemporary sense.